Sir John Monash had one more campaign to fight in 1927 before planning to retire gracefully. For over a decade there had been a groundswell of public support for a memorial to be built in Melbourne to commemorate the 19,100 Victorians who lost their lives and for the 89,000 who served in the First World War. But the form it should take and where it should be located had not reached a consensus. Monash was determined to break the impasse, just like he had broken through the stalemate on the Western Front. Having Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance built would be another defining event in his life and a project most dear to his heart.

As important a military figure as Monash is, we miss much if we only focus on Monash the general.

– General Angus Campbell, Chief of the Defence Force

Adopt as your fundamental creed that you will equip yourself for life, not solely for your own benefit but for the benefit of the whole community.

– Sir John Monash

After the end of the First World War Monash spent eight months in London successfully overseeing the repatriation of soldiers to Australian. Upon returning to Melbourne at the end of 1919, he had picked up where he had left off as a businessman. However, in 1920 he sold his business and became manager and chairman of what would become known as Victoria’s State Electricity Commission (SEC). It involved creating an open-pit mine in the Latrobe Valley of Gippsland to extract brown coal, building a generating plant, a new town for workers, and transmission lines. Monash was the ideal man for the job. It proved to be an extremely demanding role but, as usual, he rose to the challenge and in spite of technical, financial and political difficulties, electricity generation from the SEC was available in Victoria from 1924 onwards.

Sir Robert Menzies, a Victorian member of Parliament at the time and future Australian Prime Minister, recalled the time Monash was seeking additional funding for the SEC. The Cabinet had rejected his request and on hearing about it, he came to Parliament House demanding to meet with the Cabinet. The Premier, Sir William McPherson, agreed and when Monash entered the Cabinet Room, “we all stood up instinctively,” according to Menzies, such was their respect for the man. He was then given a seat at the table and said to the Premier, “I gather that the Cabinet has rejected my proposal.” When the premier replied in the affirmative, Monash said, “Well, that can only be because they have failed utterly to understand it. I will now explain it.” Menzies continues the tale:

He sat there with that rock-like look, and he explained it, and one by one, we shrivelled in our places; one by one, we became convinced, or at any rate, felt that we were convinced of the error of our ways, and for half an hour he went on. He explained this thing step by step by step and we were left silent.3

The Cabinet decision was reversed on the spot and Monash had what he wanted. The performance reminded Menzies of the Monash’s planning of the Battle of Hamel:

He was never guilty of coming to any task inadequately prepared. This characterised him, I am sure, in every aspect of his life, but above all things having done that, he had the force of character, the utter integrity, the persuasiveness of language, the clarity of vision which enabled him to take all the ideas that he had and put them clearly into the minds of other people.4

These characteristics would be the weapons he would use in the case of the National War Memorial.

War Memorials Advisory Committee

In December 1918 the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects called a meeting of interested parties to discuss how war memorials should be designed and constructed in Victoria. The War Memorials Advisory Committee was formed under the chairmanship of Sir Baldwin Spencer, professor of biology at the University of Melbourne. After some consideration the committee came out with the recommendation that Melbourne should have an Arch of Victory built in St Kilda Road just south of the city. The committee had no powers and the many towns and cities throughout Victoria wanting memorials ignored the committee’s recommendations.5

Meanwhile the Melbourne City Council were keen to have a national war memorial built after seeing what the Victorian city of Ballarat had done in designing an ‘Avenue of Honour’. A public meeting was called in September 1920 but little eventuated.6

The following year on 4 August, the Melbourne City Council again organised a public meeting where it was resolved that the memorial should be a non-utilitarian monument. Following the meeting an executive committee was formed chaired by the Lord Mayor with Sir John Monash as deputy. All committee members were experienced business leaders, senior politicians and military leaders. Monash was also on the sub-committee charged with determining the ideal site for a monument as well as being on the sub-committee to organise a competition for the design of a memorial.

A few weeks later an appeal for was launched by the Lord Mayor of Melbourne to raise £150,000 from the public. The total cost of the memorial was set to be no more than £250,000 with the Victorian Government and the Melbourne City Council each contributing £50,000.

By March 1922 the site sub-committee had agreed on an area in Domain Park known as “The Grange”, 1.3km south of the city’s central business district, as the best location. Their recommendation was accepted by the executive committee.

The same month designs for a new memorial were invited from British subjects living in Australia or Australians living overseas. The award for first prize was £1,000. A total of 83 entries were received by the October 30 deadline. A subcommittee of three persons—one being the chairman Sir John Monash—were responsible for assessing the entries.

The Shrine of Remembrance contest winner

Six finalists were short-listed and asked to submit more details and costings. On 13 December 1923 the winning entry was announced. The design, called ‘Shrine of Remembrance’, was submitted by two Melbourne-based architects, Phillip Hudson and James Wardrop. Both had served in the First World War.7

The architectural and heritage consulting firm Lovell Chen describe the design of the Shrine of Remembrance in this way:

Hudson and Wardrop’s scheme was derived from classical Greek sources in its form and detailing. It relied on careful proportioning, sensitively placed ornament and strong axial relationships to achieve its impact. The Shrine itself consisted of a square plan, granite clad building centred on a two level terrace, with steps radiating down to the north, south, east and west.8

The reaction from the public and others was mixed. The Argus and the Age newspapers were enthusiastic, as was the Herald at first. It was only when the Herald started publishing objections and alternative suggestions from artists and readers that the Herald started questioning the choice of the memorial. An editorial piece later in January 2014 called for a stop to building the Shrine, claiming:

Clearly none of the designs has satisfied those who are most competent to judge. None has satisfied even the majority of the public.9

The following month the Herald announced it was organising a plebiscite for readers to have their say:

Do You Want This? If you do not like this design for Victoria’s Shrine of Remembrance, or would prefer some other form of memorial, say so on the coupon printed in Page 1 of “The Herald”.10

The Herald’s managing editor, Keith Murdoch, had been a war correspondent in Europe in the First World War and had used his influence to try to stop Monash being made the Australian Corps commander and later tried to prevent him from being in charge of repatriation. Since taking over the editorship of the Herald in 1921 he had changed the paper from being a stodgy journal to become a populist newspaper with rapidly rising readership.11

Well-connected politically and highly ambitious, Murdoch knew that controversy sells. For the next few years he would be relentless in attacking the proposal for the Shrine of Remembrance.12

The Shrine is as dead as Julius Caesar

The Herald reported it has been receiving “hundreds of letters a day” as a result of the plebiscite. It stated the consensus of opinion was for a hospital in place of the chosen design.13]

The government of the day was not hurrying in coming forth with a decision due to other more pressing concerns, including trying to keep themselves in power. Then in July 1924 a Labor government took over and, acknowledging the Herald’s campaign, was in favour of a hospital as a memorial.

A few months later the Labor government was replaced and the idea of an arch appeared again. And so, the non-decisions and dithering went on through 1925 and into 1926.

For the Anzac Day ceremony in 1926 a temporary cenotaph was constructed. This led to another idea for a war memorial. In July word came out that consideration was being given to an alternate memorial known as Anzac Square at the corner of Bourke and Spring Streets, opposite the national Parliament House.14

The idea had been conceived by the government to save money. Initially it would be a small square with the idea of expansion in the future. The size and cost would depend on the number of properties that would need to be acquired.

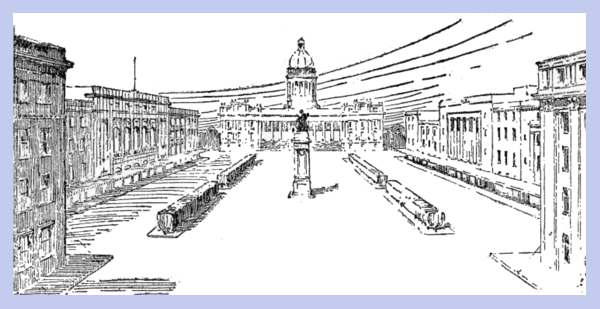

Proposed Anzac Square in Melbourne

Proposed Anzac Square in MelbourneRealising the Shrine proposal was dead, the Melbourne City Council and the leadership of the Returned Soldiers’ League (RSL) backed the new idea although there was dissent from within the membership. Monash, for one, did not agree with it but didn’t come out publicly. He would wait for the right moment.

Murdoch’s Herald and Weekly Times newspapers continued their objection to the Shrine, with the 12 March 1927 issue of the Weekly Times concluding:

[T]here can be no question that the ideal site is at the top of Bourke street, fronting Parliament House, the true centre of the national life.16

The announcement by the Melbourne City Council six days later left the Anzac Square backers dumbstruck. The council decided it could not support the favoured large Anzac Square scheme as the land resumptions alone would cost £1,000,000. Without the council support the Anzac Square was dead.

To Monash the situation was just like the one the Germans found themselves in when they overreached and weakened themselves in their 1918 ‘Project Michael’ advance into France. The Anzac Square scheme had also over-reached itself and exposed its weakness of the cost involved. Monash had purposely not led the campaign for the Shrine publicly up to this point. Now it was his time to show leadership.

Monash goes on the offensive for the Shrine

One of the gifts Monash had was the ability to take a complex subject and distill it down to the fundamentals and to clearly communicate this to his audience. His ability to relate was key. The Can-Do Wisdom Relational Domain shows diagrammatically the path from the I Can quadrant to the We-Can quadrant. Monash had to demonstrate leadership if he was going to change people’s minds.

Can-Do Wisdom Relational Domain

Can-Do Wisdom Relational DomainThe days leading up to Anzac Day in 1927 would put the spotlight on Monash and he would use it to his advantage. The week was a very big occasion for Victoria with an eleven-day Royal Visit by the Duke and Duchess of York. As well as being involved in official receptions he was chairman of the Anzac Day Commemoration Council and announced plans for the biggest Anzac Day march yet seen. He would lead the march of 28,000 returned soldiers and also take the salute with the Duke of York before addressing the commemoration service in the Exhibition Building. Thirty Victoria Cross winners from all over Australia had been invited to take part.

On the Friday evening before the Monday Anzac Day march, Monash was invited to speak at the annual Returned Soldiers’ League dinner. He was full of praise for the good work of the RSL even though the leadership was not supporting the Shrine of Remembrance proposal. In his speech he told of his experience as Corp Commander:

No other military machine could have been more powerful or more invincible. In the past few months of the war I was able to recommend 25 men for the Victoria Cross. Their acts of gallantry were almost superhuman.17

Towards the end of his speech came the opportunity to advance his cause. As part of his planning for this occasion he had arranged for 26 VC winners to be spread out across the dining room. Encouraged by Legacy’s Alfred Kemsley, they rose to applause Monash when he made his key points about a fitting war memorial as the Argus reported:

With the commemoration of Anzac Day, one naturally thinks of Victoria’s war memorial. I was a member of the committee of assessors which selected the design for the Shrine of Remembrance. It is my firm conviction that this is the only proposal worthy of the support of the soldiers of Victoria. (Applause.) When the time comes I can give you 100 good reasons why you should not consider any other form of memorial, why you should not support plans for the beautification of Melbourne at the expense of the soldier and of his war record. (Applause.) An Anzac Square is out of the question for many reasons, among them that of finance. Keep your judgment in reserve, and when you are to make it let me come and tell you in detail why you should support only the Shrine of Remembrance.” (Applause.)18

It was a short and masterful performance of persuasion of a key body of people—the soldiers who had fought in the war.

On the day after the Anzac Day march a prepared statement from Monash was published in the Argus where he expanded on the points he raised at the RSL dinner. In the lengthy article he set out the history of the competition and explained why the shrine was a fitting monument compared to the square proposal.19

In responding to Monash’s statement the same afternoon, the Herald accused Monash of being out of touch:

He has become the champion of a lost cause, the leader of a forlorn hope . . . The cold, squat block tomb, embellished though it may be with equestrian statues of Sir John Monash and other generals, appeals as little to the people at large as it does to the artists.20

There were other objections as well. The weekly Catholic publication, the Advocate, was scathing in its description of the Shrine:

The design upon which the memorial is to be erected is heavy and squat. It is uninspiring and appears cold and suggestive of a mausoleum. It lacks imaginative appeal. It oppresses and suggests something barren of hope and unsymbolical of its purpose. But, whatever the artistic shortcomings of the memorial may be, there is a far graver ground upon which opposition to it might be taken. It is alien and pagan in its whole lines and conception. It not only does not suggest the Christian spirit, but, in a marked degree, it suggests a spirit almost anti-Christian.21

They were wasting their breath. The battle was over and Monash and his followers had won, once more. On 19 May the Returned Soldiers League decided to recommend the Domain site for the Shrine of Remembrance. Monash was appointed to a sub-committee to reexamine all serious proposals. Their findings were accepted by the War Memorial Committee on 20 May. The Shrine of Remembrance was once again recommended to the State Government as the war memorial and approval was given on 12 August 1927.

Monash continued to be involved with the successful fundraising effort and in overseeing the construction of the Shrine. He died on 8 October 1931 with an estimated crowd of 250,000 mourners attending his State funeral. The building was finally completed in September 1934 and was dedicated as a memorial on Remembrance Day, 11 November 1934.

The magnificent Shire of Remembrance we know today is only there because of Sir John Monash’s tireless efforts over a decade in making real the vision for a National War Memorial of Victoria.

NOTES

- Composite Image: “File:Shrine of Remembrance 1.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, modified 1 March 2019, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shrine_of_Remembrance_1.jpg.

- Composite Image: “File:Statue of John Monash, Monash University (Clayton Campus), Melbourne 2017-10-30 02.jpg,” Wikimedia Commons, modified 1 March 2019, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Statue_of_John_Monash,_Monash_University_(Clayton_Campus),_Melbourne_2017-10-30_02.jpg.

- Robert G. Menzies, “Sir John Monash Centenary Service held at Linlithgow Avenue, Melbourne – 11th April 1965 – Speech by the Prime Minister, The Rt. Hon. Sir Robert Menzies,” PM Transcripts, Transcripts from the Prime Ministers of Australia, https://pmtranscripts.pmc.gov.au/release/transcript-1094.

- Menzies, “Sir John Monash Centenary”.

- Allan Blankfield, “General Sir John Monash,” http://stkildashule.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/General-Sir-John-Monash.pdf.

- “National War Memorial,” The Herald, Sept 16, 1920, 18.

- Peter Lovell, Shrine of Remembrance, St Kilda Road, Melbourne, Conservation Management Plan (Melbourne: Lovell Chen, 2010), 11.

- Lovell, Shrine of Remembrance, 12.

- “Is the Memorial the Best We Can Raise?” The Herald, Jan 26, 1924, 6.

- “The War Memorial Plebiscite,” The Herald, Feb 18, 1924, 6.

- Geoffrey Serle, “Murdoch, Sir Keith Arthur (1885–1952),” Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/murdoch-sir-keith-arthur-7693/text13467, published first in hardcopy 1986, accessed online 10 March 2019.

- Bruce Scates, A Place to Remember: A History of the Shrine of Remembrance (Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 22.

- “War Memorial Plebiscite Letters,” The Herald, Feb 23, 1924, 13.

- “Changed War Memorial Scheme Favored,” The Herald, July 3, 1926, 1.

- “Proposed Anzac Square in Melbourne,” The Daily News, March 31, 1927, 2.

- “Our War Memorial” Weekly Times, 12 March 12, 1927, 38.

- “Spirit of Anzac,” The Argus, April 25, 1927, 14.

- “Spirit of Anzac”, 14.

- “A War Memorial,” The Age, April 27, 1927, 13.

- “Lesson of Cenotaph,” The Herald, April 27, 7.

- “That ‘National War Memorial’,” The Advocate, May 26, 1927, 27.