The Can-Do Wisdom Framework for Change shown below didn’t appear overnight. The Knowledge Visualization model I developed is the result of many years of study and builds on the work of many individuals. This is the story of its origins and development over the past twenty years.

A picture is worth a thousand words.

– UnknownIt is our choices, Harry, that show what we truly are, far more than our abilities.

– J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

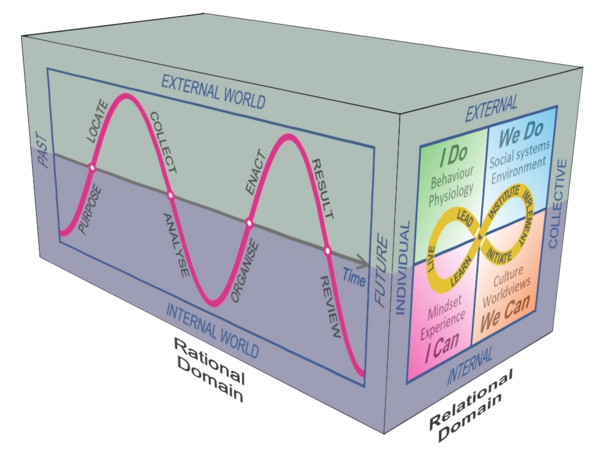

I often use diagrams, such Figure 1 above, to explain complex processes and there nothing more complex than ourselves and the world we live in.

My preferred learning style is that of a visual learner. I’m always sketching things I would like to build and generally it’s diagrams that get my attention more than words.

This story and the sequence of visualizations demonstrates learning, living and leading for a new way of explaining the change process. It’s also an example of the result of a Knowledge Visualization process.

What is Knowledge Visualization?

Burkhard defines Knowledge Visualization as “the use of visual representations to improve the transfer of knowledge between at least two persons or group of persons.”[1]

While Knowledge Visualization is of growing interest as a discipline of study, it’s not a new idea. Aboriginal rock art in parts of northern Australia date back tens of thousands of years. The paintings and carvings depict subjects ranging from ancestral spirits to animals now extinct.

This cave art was part of community story-telling and knowledge sharing. As evolutionary biologist Alice Roberts points out, these stories “could contain useful information – about the landscape, animals or society – extending human experience beyond a single lifetime.”[2]

My initial efforts in explaining rational thinking

The initial information processing model that I used in my sales and marketing training programs from 1992 through 1998 was based on three words: discover, develop and deliver. Clients were advised, “To achieve your mission or purpose you need to discover what is needed, develop answers, and then deliver.”

We would then go on together to explore each of these phases in coming up with action plans.

As Principal of my consultancy firm, Woodlawn Marketing Services, it was my mission to assist SMEs (small to medium enterprises) in discovering, developing, and delivering what their clients wanted.

The way I usually helped clients was by guiding owners and managers through the decision-making process and by conducting research for the discovery phase.

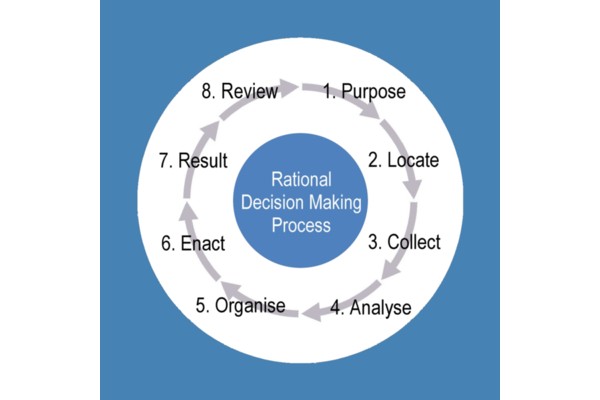

The typical text-book approach to the rational decision-making process involves steps such as:

- Purpose – Identify the problem

- Locate – Identify information sources

- Collect – the data

- Analyse – assess meaning from data

- Organise – create alternatives, assess and choose

- Enact – put into action

- Result – monitor result of action

- Review – reflect and learn from result and process used

These steps can be visualised as a circular process model as shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2 – Rational Decision-Making Process

Figure 2 – Rational Decision-Making ProcessThe process as described is logical, makes common sense, and it’s actually used every day in formal decision-making and problem-solving situations. Over the last 60 years thousands of companies and individuals (including me) have been trained in the Kepner-Tregoe decision-analysis method.[3]

Smoke alarms, computer programs and robots also operate using decision logic and until recently we’ve been erroneously told that our minds work like computers. Even in a 2005 interview, Ben Tregoe, co-founder of Kepner-Tregoe, referred to the computer in a person’s brain.[4]

However, there’s no avoiding subjective aspects and emotions when people are involved in decision making. It’s often said that following the rational decision-making process is only done to justify their choice and to be able to say it was a rational decision.

Others have investigated the way we actually make decisions. Psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman researched aspects of judgment and decision making resulting in Kahneman being awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 2002.[5]

Dan Arielly[6] is another psychologist who has explored irrational behaviour, while Gary Kline has studied the use of intuition in decision making.[7]

John Boyd’s OODA Loop

My first attempt at developing a useful decision-making model in 2001 was derived from the work of John Boyd (1927–1997). Boyd, an ex-fighter pilot in the U.S. Air Force, is famous for developing the OODA Loop model of decision making where OODA means Observe, Orient, Decide and Act.

Figure 3 – Simplified Sketch of OODA Loop

Figure 3 – Simplified Sketch of OODA LoopBoyd’s major contributions with the OODA Loop were recognising the importance of unhindered observations (Observe phase) and identifying human aspects in the Orient phase that complicate decision making.

Frans Osinga, author and an officer of the Royal Netherlands Air Force, points out there is another key aspect of Boyd that isn’t appreciated. While he left no writings explaining his thinking, his briefings and slides are important because they show how OODA operates as a model for personal learning.[8]

Randall Whitaker adds to Boyd

A major development in my thinking of a workable decision-making model came about in 2001 after I saw Randall Whitaker’s adaption of John Boyd’s OODA Loop as a Problem Solving Cycle[9] shown below.

Figure 4 – Randall Whitaker’s Problem Solving Cycle

Figure 4 – Randall Whitaker’s Problem Solving CycleI made an important addition to Whitaker’s model to recognise that our depictions of the external world and our enactments are influenced by a mindset made up of our existing factual and procedural knowledge, by our existing mental models and by our core values and purpose.

Karl Wiig made the point that without these human aspects, rational decision-making model fails:

Increased understanding leads us to realize how we have misunderstood the way people handle situations and make decisions by believing that decision-making is a rational and often conscious deliberation.[10]

The problem for many individuals is that bottlenecks occur causing ‘friction’, which interrupts or distorts the flow of information to and from the individual’s internal world. Whitaker called these the Depiction Bottleneck and the Enactment Bottleneck. These bottlenecks occur when information is moving across the interface between our internal world and the external world (refer to Figure 4). Some of these are the result of external influences while most are internal personal deficiencies.

Whitaker’s problem-solving cycle only shows two transitions between the Task Venue and the Depictive Venue. I extended the cycle to include two more transitions, calling these additional ones the Initiation bottleneck and the Appraisal bottleneck.

It ended up in being a very busy slide – not ideal!

Figure 5 – Delta Control Loop

Figure 5 – Delta Control Loop

Figure 6 – Can-Do Wisdom Rational Domain

In Part 2 I have described the ‘friction’ that can occur due to the four bottlenecks.

The Relational Domain comes into being

So, what happened the mindset label of existing knowledge, mental models, and values that appeared in Figure 5?

In 2003 I took the view there was a force-field operating along the Time axis of the rational domain. I imagined taking a slice as if it was an MRI scan showing a view back down the Time axis.

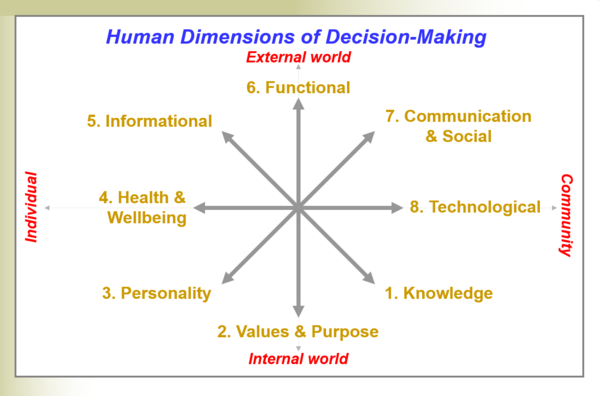

The forces helping or hindering the efficiency and effectiveness of the decision-making process were what I called “informationist” competencies, where an informationist is defined as “a person who — in collaboration with others — is skilled in obtaining, organising, analysing, interpreting, and using information for the purpose of solving problems, for learning, and for anticipating possible futures.”

By 2005 my view had expanded to eight human dimensions involving an individual and the community. These are the eight force-fields which help or hinder performance.

Figure 7 – Human Dimensions of Decision-Making

Figure 7 – Human Dimensions of Decision-MakingKen Wilber’s Integral Theory

I first came across the writings of philosopher Ken Wilber in 2002. They struck me as being highly esoteric discussions of human consciousness and I wasn’t ready for that.

However, when knowledge management expert Luke Naismith pointed me to Wilber’s four quadrants model[11] in 2005, I immediately recognized the similar structure of internal-external and individual-collective:

How Can-Do Wisdom evolved

In 2012 I came across an article on the use of Wilber’s four quadrants in business settings. It described the path used in moving through the quadrants:

I use a pattern called the Z . . . you start in the upper left hand corner, to the upper right hand corner, to lower left and then to lower right. In my mind it’s actually a figure 8 because the lower right impacts the upper left if you’re being holistic with how you live your life.[12]

A figure 8 turned 90 degrees becomes an infinity symbol so I incorporated this into the Human Dimensions Domain visual as a pathway through all four quadrants:

Two years later I read Daryl Paulson’s book, Competitive Business, Caring Business. In the book, Paulson discussed how Wilber’s four quadrants could be applied to business in an integral manner using all four quadrants. This sentence, in particular, jumped out at me with its reference to wisdom:

Integral business is about care, concern, wisdom, fairness, character, truthfulness—and making a profit. But, it does not sell out to profit only, a position no longer acceptable in today’s world.[13]

Paulson was not the only person to relate wisdom to Wilber’s ‘Integral Theory’, based on the four quadrants.

Copthorne Macdonald wrote an essay on moving from the industrial age to an integral age. By taking a broader perspective, using the four quadrants, Macdonald suggested that “wise people see the world and process the data of life leads them to exhibit a whole array of better-than-ordinary ways of being, living, and dealing with the world.”[14]

In 2015 I started work on labelling the infinity path. I had the answer for the individual pathway, Learn – Live – Lead, when I read an article posted by leadership coach Jill Poulton:

Effective leaders are always engaged in this paradigm of learning cycle: learn it, live it, lead it.[15]

Learn, Live, Lead happens to be the motto of the high school I had attended, De La Salle College, so it was an easy choice to adopt these labels for my model.

It took a while longer to settle on the labels for the collective but eventually I found the answer in this passage giving a simplified overview of the change process:

Initiation is the first stage of the process leading to a decision to proceed with a change. From then, the implementation stage covers the experience of attempting to put the change into practice. Finally, the institutionalisation stage refers to the way the change becomes built into normal practice and is no longer perceived as anything new.[16]

This brought me in 2016 to the current version of the Can-Do Wisdom Relational domain:

Figure 9 – Can-Do Wisdom Relational domain

Figure 9 – Can-Do Wisdom Relational domainWhile the time period of the duration for a cycle through the Rational domain can be a second or a day or longer, the time axis for the Relational domain is vertical to the page and stretches back in time to the ‘Big Bang’. Not only is the ‘Learn, Live , Lead, Initiate, Implement and Institute’ sequence the pathway we can take today, but the infinity symbol represents the whole of creation to date. David Christian explains this in his book, Big History.[17]

Another way of understanding evolution of the Relational domain is through the work of Arthur Koestler. In his book, The Ghost in the Machine, he describes a holon — something that is simultaneously a whole and a part. For example, letters, words, phrases and sentences are all holons. Koestler adds, “So are cells, tissues, organs; families, clans, tribes.”[18]

Creation and destruction

During one of his many lengthy briefing sessions, John Boyd made this point:

We can’t just look at our own personal experiences or use the same mental recipes over and over again; we’ve got to look at other disciplines and activities and relate or connect them to what we know from our experiences and the strategic world we live in.[19]

Boyd’s favourite example of creation and destruction was an exercise he gave to his audience. It went along like this: Imagine four difference scenes: a skier on a ski slope; an outboard motor boat on a lake; a bicycle rider on a pathway; and a boy with a toy tank with rubber caterpillar treads.

What do you see in each of these scenes? What’s the breakdown of components or elements that make up these scenes? (This is the analysis phase.)

In what way could some of these elements be rearranged into something completely different?

Boyd takes the skis, the outboard motor, the handlebars, and the rubber treads and produces what? (This is the synthesis phase.)

The answer: A snowmobile!

Can-Do Wisdom Framework

What I have done over the last 20 years is to pull apart concepts that others have developed (analysis) and put them back in new combinations (synthesis). Many of the results didn’t work out and were discarded.

I was finally able to bring the two domains together by combining conceptual diagrams of the Rational Domain and the Relational Domain into a visual metaphor of a rectangular box to become the Can-Do Wisdom Framework.

Figure 10 – Can-Do Wisdom Framework

Figure 10 – Can-Do Wisdom FrameworkMy Knowledge Visualization work is still not over yet. Stefan Bertschi et al. describe the Knowledge Visualization process steps as:

. . . gathering, interpreting, developing an understanding, organizing, designing, and communicating the information. While the previous sentence implies a linear flow, it is hardly a linear process. In fact, any step can link to any other step in any number of iterations until a “final” representation is created. Of course, it never is quite final.[20]

In the end Knowledge Visualization is an important tool for a leader in the I Do quadrant trying to influence the collective in the We Can quadrant to initiate a program or change of some kind by transferring knowledge.

Notes

- Remo Aslak Burkhard, “Learning from Architects: The Difference Between Knowledge Visualization and Information Visualization,” in Proceedings. Eighth International Conference on Information Visualisation, 2004: IV 2004, London, 16 July 2004. doi: 10.1109/IV.2004.1320194.

- Alice Roberts, The Incredible Human Journey (London: Bloomsbury, 2009).

- Charles H. Kepner and Benjamin B. Tregoe, The Rational Manager: A Systematic Approach to Problem Solving and Decision Making (Princeton, N.J.: Kepner-Tregoe Inc., 1965).

- “Interview with Ben Tregoe. Part 1. The Origins of KT Rational Process,” Kepner-Tregoe. https://www.kepner-tregoe.com/tools/videos/the-thinking-organization/the-origins-of-kt-rational-process-part-1/.

- “Daniel Kahneman Biographical,” NobelPrize.org, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2002/kahneman/biographical/.

- Dan Ariely, Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces that Shape Our Decisions, Revised and expanded edition (New York: Harper Perennial, 2010).

- Gary Klein, The Power of Intuition: How to Use Gut Feelings to Make Better Decisions at Work (New York: Currency Books, 2004).

- Frans P.B. Osinga, Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd (New York: Routledge, 2007), 46.

- Whitaker, Randall, “Managing Context in Enterprise Knowledge Processes,” in The Strategic Management of Intellectual Capital, ed. David A. Klein (Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann), 75.

- Karl M. Wiig, “A knowledge model for situation‐handling”, Journal of Knowledge Management 7, no. 5 (2003): 6-24, doi: 10.1108/13673270310505340.

- Ken Wilber, A Brief History of Everything (Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications, 2000), 65.

- Russ Volckmann, “A Fresh Perspective: Changing Self and World – An Interview with John Smith,” Integral Leadership Review 6, no. 4 (2006).

- Daryl S. Paulson, Competitive Business, Caring Business: An Integral Business Perspective for the 21st Century (New York: Paraview Press, 2002), 131.

- Copthorne Macdonald, “Deep Understanding: Wisdom for an Integral Age,” Journal of Conscious Evolution 2, no. 2 (2006), https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol2/iss2/11.

- Jill Poulton, “Learn. Live. Lead.” Destination by Design Coaching and Consulting, accessed June 30, 2015, http://www.destinationbydesigncoaching.com/.

- Mike Wallace and Keith Pocklington, Managing Complex Educational Change: Large Scale Reorganisation of Schools (London: RoutledgeFalmer, 2002), 58.

- David Christian, Big History: The Big Bang, Life on Earth, and the Rise of Humanity (Chantilly, Virginia: The Great Courses, 2008).

- Arthur Koestler, The Ghost in the Machine (New York: Random House, 1976).

- John R. Boyd, “The Strategic Game of ? And ?” Lecture given in 1978, slides edited by Chet Richards and Chuck Spinney, http://www.dnipogo.org/boyd/strategic_game.pdf.

- Stefan Bertschi et al., “What is Knowledge Visualization? Perspectives on an Emerging Discipline,” in Proceedings, 15th International Conference on Information Visualisation, London, July 13-15, 2011. doi: 10.1109/IV.2011.58.