Was Al Dunlap, the CEO who sent Sunbeam Corp into bankruptcy, a corporate psychopath? Corporate psychopaths, or workplace psychopaths, are those people in management positions with an “uncaring, callous and an unemotional attitude towards others” while engaging in “pathological lying, extreme manipulation and actions often associated with criminality.”1

This is Part II of a two-part series examining the damage corporate psychopaths cause to organisations and their stakeholders. See Part I: How Al Dunlap came to destroy Sunbeam Corporation.

People generally cannot believe themselves so easily manipulated and controllable.

This is precisely why they are so easy to manipulate and control.

——.Bryan Key Wilson, PhD, author of The Age of Manipulation.

Psychopaths can exhibit dysfunctional behaviours on a spectrum ranging from very severe to mild. Very severe cases are those individuals who cannot relate properly with others and are often incarcerated or institutionalised because of their behaviour. Mild cases in management ranks in an organisation are those “incompetent managers whose poor management skills create disarray, demoralisation and disorganisation, the result of which is that the workplaces they are trying to manage become toxic.”2

It is suggested that 1 percent of the population has psychopathy — someone without empathy.3 Therefore it’s not really surprising that you will find such people employed in a wide range of occupations. What’s new is that we now have a term a term for a psychopath in an organisation – the corporate psychopath — and a growing number of studies of their potential for destructive behaviour.

Note that because it is a mental condition, it’s not illegal to be a psychopath – they can’t help it.4 It’s only when a psychopath’s behaviours are unlawful that the law intervenes.

Psychologists Paul Babiak and Robert Hare suggest you can’t assume your boss is a psychopath just because some behaviours fit that of a psychopath. They can only be properly identified by using a standardised diagnostic instrument whereby expert observers can assess the presence of psychopathic personality disorder.5

However, observations of psychopathic behaviours are a clear warning sign of the potential presence of a psychopath or that of an incompetent manager. Both can do damage to an organisation and the people in it.

Warning signs of the presence of a workplace psychopath

The most obvious sign of the presence of a workplace psychopath is where talented people leave an organisation after the arrival of a new manager. It can take some time before exits take place but there are earlier warning signs available if more senior managers care to look.

Professor Manfred de Vries, a psychoanalyst, suggests a red flag would be one where the following situation exists in an organisation:

A glaring discrepancy between how direct reports and junior employees perceive an executive and how that executive’s peers or boss perceive him or her. Lower-level employees are often on the receiving end of a boss’s psychopathic behavior and usually spot a problem much sooner than senior management.6

Lawsuits, especially those involving bullying behaviour, should also require a close look at the particular manager involved.7

Day-to-day behaviours of a workplace psychopath

One of the earliest signs of the entry of a psychopath in where a new manager makes wholesale changes to the way things have traditionally been done — without any logical basis for doing so. This new manager comes across as knowing ‘everything’ and announces there will be better ways of doing things.

Further changes will be made without any consultation. Innovations the previous manager may have introduced will be discarded. Talk of “we used to do this” will be outlawed. This is a very unsettling and confusing time for subordinates and other stakeholders.

But there’s more to follow. Suddenly the micromanager appears. The manager will need to approve actions and require constant reporting by subordinates. This manager wants to be in full control, to make every decision but to shift the blame to others if things go wrong. And things will go wrong because many of the “thought-bubble” changes and developments won’t be delivered anyway — it’s all smoke and mirrors. Or, as some say, it’s all about theatre.8

Meanwhile the workplace psychopath is busy working on developing their network of information providers and supporters while also identifying any potential impediments to their goal of power and prestige.

One of the methods used by psychopaths is use “confidentiality” liberally so as to limit subordinates and others sharing information, as well as using one-on-one conversations to divide and conquer as Babiak and Hare explain:

Specifically, their game plans involved manipulating communication networks to enhance their own reputation, to disparage others, and to create conflicts and rivalries among organization members, thereby keeping them from sharing information that might uncover the deceit.9

Initially subordinates and others in the organisation will be impressed by the charm and enjoy the friendship of this seemingly bright, confident and successful individual. They are in fact the unwitting pawns to be used by the psychopath and when no longer useful will be discarded.

Expect to see overstated claims of successes and lies. While a normal person telling lies would exhibit some stress and become emotionally involved — such as raising their voice or touching their ear lobe — the psychopath shows no emotion. They will even tell more elaborate lies and leave us completely confused.10

Even though they lack empathy — after all they have no interest in the welfare of the subordinates they may bully, berate and force out of the organisation — psychopaths are still able to fake the impression of empathic behaviour when they need to, especially for their information providers and supporters — the pawns.11

The impact of a workplace psychopath

Benedict Sheehy, Professor of Law at Canberra Law School, and colleagues describe the impact of psychopath in this way:

Psychopathy is a major problem for the performance of organisations, affecting productivity, long-term stability and especially the health and wellbeing of employees being supervised by managers with psychopathic traits.12

It’s only in the last 20 years or so that academic researchers have begun to study in earnest the effects of psychopaths on organisations and the findings are disturbing.13

A workplace psychopath has an impact on both the organisation, employees and stakeholders.

A drop in productivity is very common when a workplace psychopath is present. As one employee explained to a researcher, “We all started spending a lot of time talking about what she was trying to achieve, rather than doing our jobs.”14

Professor Clive Boddy, an expert in the field of corporate psychopathy, says there is a high correlation between bullying and psychopathy, adding that psychopaths are “ruthless towards other people and totally devoted to self-orientation and self-promotion.”15

Families and friends of affected employees will notice a change but may not be told what’s going on. This can have an adverse effect on personal relationships even to the point of breakdown.

Another aspect senior management may come to realise too late is that corporate psychopaths have been found to engage in financial fraud and CV fraud.16

Protection for the workplace psychopath

Workplace psychopaths are easily able to enter into an organisation and progress through management ranks when they have been able to charm key senior managers and other influencers into becoming patrons. This often short-circuits the normal recruitment process which means a thorough assessment of the background of the employee is not carried out.

Babiak and Hare describe the role of the patron in protecting these psychopaths:

Patrons are influential executives who take talented employees “under their wing” and help them progress through the organization. Once this patronage is established, it is difficult to overcome. With a patron on their side, psychopaths could do almost no wrong. Powerful organizational patrons (unwittingly) protect and defend psychopaths from the criticism of others. These individuals would eventually provide a strong voice in support of the psychopaths’ career advancement vis-a-vis promotions and inclusion on corporate succession plans.17

Not everyone in the organization is taken in by the psychopath — they see through the lies and over-blown self-promotion. But because of this patronage, mentions about violations of company policy, and raising issues about “questionable” interpersonal behavior, such as bullying, would be effectively buried.

The presence of a workplace psychopath in an organisation will have consequences that are visible and real. While sometimes a hard-nosed manager may seem to be needed to lead an organisation out of trouble in the short term, a workplace or corporate psychopath at CEO level is more likely to cause significant problems and even destroy an organisation in the long-term.

It’s not uncommon to experience bosses who are described as “tough”. Think of Kerry Packer or Rupert Murdoch. But are they necessarily corporate psychopaths just because they might be cold, hard-driving, and ruthless? We don’t know for sure without a proper assessment by a psychologist trained in the use of such diagnostic instruments.

Measuring Psychopathy

Canadian psychologist, Dr Robert Hare, is recognised as an expert in analysing psychopaths. From his experience over decades, Hare suggests that 1 percent of the population are psychopaths, while a greater percent of CEOs would be classified as corporate psychopaths.18

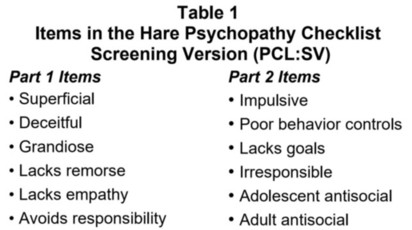

Hare’s Psychopath Check List (PCL-R) has become the international standard for the clinical assessment of psychopathy. Originally developed for assessing individuals exhibiting criminal behaviour, there is also a simpler Screening Version (PCL:SV) used for cases of suspected corporate psychopaths.19

According to Hare, the PCL:SV comprises 12 items, each reflecting a different symptom or characteristic of psychopathy (see Table 1).

Items are rated on a 3-point scale (0 = item doesn’t apply, 1 = item applies somewhat, 2 = item definitely applies). The items are summed to yield total scores, ranging from 0 to 24, that reflect the degree to which an individual resembles the prototypical psychopath. A cutoff score of 19 or greater is used to diagnose psychopathy.

Was Al Dunlap a Corporate Psychopath?

One of the first times it was suggested Al Dunlap could be a psychopath was in a 2005 Fast Company article, “Is Your Boss a Psychopath?”20

Subsequently, journalist Jon Ronson interviewed Dunlap at his home in Florida long after he was sacked from Sunbeam. The first thing Ronson noticed was his grandiose manner and self-belief:

His inflated ego and exaggerated regard for his own abilities are remarkable, given the facts of his life. “If you don’t believe in yourself, nobody else will. You’ve got to believe in you.”21

Ronson took Dunlap through Hare’s check list of 20 traits of a psychopath (PCL-R) with a surprising result:

He admitted to many, many items on the checklist, but redefined them as leadership positives. So ‘manipulation’ was another way of saying ‘leadership.’ ‘Grandiose sense of self worth’ — which would have been a hard one for him to deny because he was standing underneath a giant oil painting of himself — was, you know, ‘You’ve got to like yourself if you’re going to be a success.’22

Even Dunlap himself believed in his over-inflated sense of self-importance. As he said in his book, Mean Business, “I’m a superstar in my field, much like Michael Jordan in basketball and Bruce Springsteen in rock ’n’ roll. My pay should be compared to superstars in other fields, not to the average CEO.”23

And when we consider Dunlap’s life and his actions as described by John Byrne and others in the previous blog post — How Al Dunlap came to destroy Sunbeam Corporation — it tells us a lot about Dunlap’s destructive behaviour. It is easy to see that he would rate highly for Part 1 items in the PLC:SV, namely, being superficial, grandiose, deceitful, lacking remorse, lacking empathy and not accepting responsibility. These behaviours were apparent not only in his business life but in his personal life as well. On that basis, one could say Al Dunlap was most likely a corporate psychopath.

So how was that Dunlap was feted as this great turnaround guru and seen as the saviour of Sunbeam Corp? It was largely because Dunlap had carefully stage managed his life and achievements.

The hidden life of Al Dunlap

When Sunbeam hired Al Dunlap very little was known about the life he had carefully managed to hide. Much of this would only come out after the demise of Sunbeam with the publication in 1999 of Chainsaw, the unauthorised biography of Dunlap by John Byrne and what later investigations showed.

Albert John Dunlap in born in Hoboken, New Jersey on July 26, 1937. Dunlap changed the story of his upbringing apparently to enhance his image as a poor boy who made good. He claimed he was “the deprived son of a Woolworth’s store clerk and a dock worker” when he actually came from a comfortable family situation.24

His younger sister, Denise, later explained their father was not a dock worker but a boilermaker at United Engineers which built power plants and their mother was a home maker. They were actually quite well off.

It seems he was a good student and a solidly-built athlete while at high school which no doubt helped after he graduated in 1956 to be selected to go to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. But he did have a foul temper as a teenager which would continue throughout his life. This was probably reinforced by his experience of bastardisation (hazing) by senior students at the Academy. In his 1966 book, Mean Business, he recalls his time at West Point:

The Point was extraordinarily difficult. It looked glamorous on the outside, but inside there was nothing but hard work. . . I was ill-prepared for the military life. The two biggest drawbacks for me at the Point were that I couldn’t march worth a damn and that I never wanted to be an engineer, the primary career for which cadets at the Academy were trained. Frankly, I hated engineering. I wanted to be a lawyer, actually. I was drawn to its competitive, adversarial nature and saw the law as a way of putting my verbal skills to effective use.25

He graduated in 1960, 527th out of his cadet class of 550 with an engineering degree. He then went on qualify as a paratrooper and was stationed at a nuclear missile site in Maryland for the next three years.

In 1961 while still serving in the army he married a nineteen year old model, Gwyn Donnelly. It didn’t take long for Gwyn to discover her husband was an angry and sometimes tortured individual. It was only decades later that the extent of the domestic violence that she had endured—both mental and physical —became publicly known. One example was detailed in her 1965 divorce complaint:

Coming home from work, he would conduct military-like inspections of the house, ducking his head under the mattress of the bed and moving chairs away from the walls to see if he could find even a trace of dust. If he did, Dunlap went ballistic. When she told him she was pregnant in May 1962, according to the complaint, Dunlap became violent. He told her he would divorce her and move to Europe so he “would not have to support you and your brat,” the complaint alleged.26

By the end of 1964 Gwen had enough of the death threats and physical mistreatment and left home with their two-year old son, Troy, for good. Dunlap didn’t contest the accusations in court, which the judge described as “extreme cruelty”, and a divorce was granted in November 1966.27

By then he had decided that the military wasn’t for him and he had started on a business career in 1963 that would see him gradually rise through the ranks to eventually be in charge of organisations and do what he liked.

Meanwhile he had lost a wife and had also cut ties with his family. Once he first became married he had little to do with his parents or sister. He would send a card to his mother for her birthday but that was generally all the contact he had. He didn’t even go to their funerals as he was “too busy”. He had little to do with his son, Troy, after his first marriage ended. And when his sister asked if he could help out when their mother needed care, he refused.

His first role as a CEO came in 1982 when he arrived at Lily-Tulip Inc., a producer of disposable cups and plates:

He got rid of 20 percent of Lily’s staff, 40 percent of its suppliers, and half of its management. In three years, he fired eleven of the company’s top thirteen executives. After a $10.8 million loss in 1982, Lily earned $8.3 million in 1983 and $22.6 million in 1984.28

By now married to second wife, Judy, he was starting to be recognised as a turnaround specialist. Next, we find him taking on international assignments for Sir James Goldsmith, followed by Kerry Packer at Australian Consolidated Press, where he would refine his slash and burn techniques. He returned to the USA in 1993 with more than enough money for retirement.

In 1994 he was recruited to take on the CEO role at Scott Paper, based in Philadelphia. The company was in decline. It had “lost market share for four years in a row and posted a loss of $277 million in 1993.”29

Dunlap was looked upon as the ideal candidate. There was a problem, though. Dunlap had conveniently kept hidden from his resume two relevant positions back in the 1970’s and the executive search company, SpencerStuart, overlooked these gaps in his employment history. It only came to light in 2001 that he had been fired in late 1973 from Max Phillips & Sons after seven weeks for “neglecting his duties” and hurting the company’s business. The second and more serious omission was Dunlap’s appointment in May 1974 as president of Nitec in New York State. Under Dunlap’s leadership Nitec posted a profit in 1976. But he was fired shortly after because of his grating management style.30

It was only after he left that an audit found that there was no profit at all but instead a $5.5 million loss. As reported in the 2001 article in the New York Times, “The auditors found evidence of expenses that were left off the books, of overstated inventory and nonexistent sales.”31

Dunlap was sued and the ensuing court cases dragged on for years, only coming to an end in 1983 after Nitec went bankrupt. He denied any involvement in the fraud, saying he did not have a “strong financial background” and blamed the accountant.32

His time at Scott Paper would make him famous as a turnaround specialist and extremely rich. But his prescription for Scott Paper’s woes would be brutal just like it would be for Sunbeam.

And while news of the closing of Scott Paper plants around the country mostly wasn’t welcomed in the local communities, Dunlap himself was feted in the media as a “master manager, with articles that dispensed his advice and wisdom on management, executive pay, corporate governance, and the economy.”33 He welcomed all the attention.

When, in July 1995, Kimberly-Clark purchased Scott Paper for $9.4 billion, the shareholders “saw their investment in the company rise by 22 5 percent. Under Dunlap’s leadership, the company’s market capitalization went up by an extraordinary $6.3 billion.”34

It was now time for Dunlap to move on. He was acknowledged in the business press as the hero of Wall Street and claimed his $100 million payout was justified. Dunlap was fortunate with the timing of the sale. It turned out that the projected income for the fourth quarter of 1995 of $100 million turned into a loss of $60 million.

Kimberly-Clark had paid far too much and would spend a massive amount in further restructuring the business over the next three years.

It was a forerunner of what he would do at Sunbeam — only this time he would be caught out.

What can we learn from the Al Dunlap Story?

Queensland-based consultant forensic psychologist Dr Nathan Brooks recommends that businesses revise their recruitment screening process, warning of the dangers of hiring “successful psychopaths” as a result of prioritising skills above personality traits when considering candidates.35

In a similar vein, Professor Karen Landay from the University of Missouri recommends that “talking with a person’s peers, subordinates and supervisors offers greater insight about a person’s leadership style and personality.” She adds, “How leaders treat people in their organizations can have long-term implications. If leaders are aggressive or threatening, it’s going to result in higher stress and turnover among workers.”36

This has important implications for organisations as they will likely face legal claims for workplace bullying. By law, organisations must provide a safe workplace.

Harvard University’s Barbara Kellerman is critical of those individuals who allowed Dunlap to cause such chaos and misery:

Al Dunlap, former chairman of the Sunbeam Corporation, could not have been so outrageously callous had he not been surrounded by deferential aides, a pliant board, and complacent stockholders, all of whom let him get away with being bad.37

Sheehy et al., writing from a legal perspective, expand on this warning to board directors:

Ultimately, responsibility for monitoring and control of the executive rests with a Board of Directors. No board can escape responsibility for a failing organisation. The law of directors’ duties makes it clear that the job of the director is not honorary. Rather, it is to ask the hard questions, make the hard calls and make the right decisions in response. It requires sceptical smelling of the wind, not burying information, nor excusing questionable behaviour on the basis of promises, nor turning a blind eye.38

Why did his Wall Street patrons and the Sunbeam board support Dunlap for so long? It simply came down to greed and self-interest. The same story would be repeated with the Enron debacle and the financial crisis of 2008. That’s another story about corporate psychopaths.

Notes

- Benedict Sheehy, Clive Boddy, and Brendon Murphy, “Corporate law and corporate psychopaths,” Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law Volume Number, 28. Issue Number, 4 (2021): 491, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9090396/.

- Sheehy, Boddy and Murphy, “Corporate law and corporate psychopaths,” 481.

- Paul Babiak and Robert D. Hare, Snakes in Suits: Understanding and surviving the psychopaths in your office, rev. ed. (New York: Harper Collins, 2019), Kindle.

- Sheehy, Boddy and Murphy, “Corporate law and corporate psychopaths,” 491.

- Babiak and Hare, Snakes in Suits.

- Manfred F.R. Kets de Vries, “Is Your Boss a Psychopath?” Harvard Business Review, Jan 7, 2014, https://hbr.org/2014/01/is-your-boss-a-psychopath.

- David Gillespie, Taming Toxic People: The science of identifying and dealing with psychopaths at work and at home (Sydney: Macmillan Australia, 2017), chap. 6, Kindle.

- Sam Vaknin, Malignant Self Love: Narcissism Revisited (Skopje, North Macedonia: Narcissus Publications, 2015).

- Babiak and Hare, Snakes in Suits.

- Thomas Erikson, Surrounded by Psychopaths: How to protect yourself from being manipulated and exploited in business (and in life) (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2020), Kindle.

- Erikson, Surrounded by Psychopaths.

- Sheehy, Boddy and Murphy, “Corporate law and corporate psychopaths,” 480.

- Clive R. Boddy, Corporate Psychopaths: Organisational Destroyers (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 6.

- Gillespie, Taming Toxic People.

- Sana Qadar, “Workplace bullies—and corporate psychopaths,” February 9, 2020, in All in the Mind, Sydney: ABC Radio National, https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/allinthemind/workplace-bullies%e2%80%94and-corporate-psychopaths/11882820.

- “Corporate Psychopaths and Fraud,” Corporate Psychopaths Research Association, http://corporatepsychopaths.org/corporate-psychopaths-and-fraud.

- Babiak and Hare, Snakes in Suits.

- Babiak and Hare, Snakes in Suits, chap 2.

- David J. Cooke et al. “Evaluating the Screening Version of the Hare Psychopathy Checklist—Revised (PCL:SV): An Item Response Theory Analysis,” Psychological Assessment 11, no. 1 (1999): 3-13.

- Alan Deutschman, “Is Your Boss a Psychopath?” Fact Company, July 1, 2005, https://www.fastcompany.com/53247/your-boss-psychopath.

- Jon Ronson, “Your Boss Actually Is a Psycho,” GQ, December 18, 2015, https://www.gq.com/story/your-boss-is-a-psycho-jon-ronson.

- “A Psychopath Walks Into A Room. Can You Tell?” NPR, May 21, 2011, https://www.npr.org/2011/05/21/136462824/a-psychopath-walks-into-a-room-can-you-tell.

- Albert J. Dunlap, Mean Business: How I save bad companies and make good companies great (New York: Random House, 1996, 21).

- John A. Byrne, Chainsaw: The Notorious Career of Al Dunlap in the Era of Profit-at-Any-Price (New York: Harper Business, 1999, 97).

- Dunlap, Mean Business, 110.

- Byrne, Chainsaw, 101.

- Byrne, Chainsaw, 104.

- Byrne, Chainsaw, 22.

- Byrne, Chainsaw, 25.

- Floyd Norris, “The Incomplete Résumé: A special report.; An Executive’s Missing Years: Papering Over Past Problems,” The New York Times, July 16, 2001.

- Norris, “The Incomplete Résumé”.

- Norris, “The Incomplete Résumé”.

- Byrne, Chainsaw31.

- Byrne, Chainsaw, 31.

- Katarina Fritzon et al. “Problem Personalities in the Workplace: Development of the Corporate Personality Inventory,” in Psychology and Law in Europe : When West Meets East, ed. Ray Bull, et al., Chapman & Hall/CRC Press, 2016.

- Marcus Credé, Peter Harms and Angie Hunt, “No, we’re not all working for a bunch of psychopaths,” Iowa State University, Oct 15, 2018, https://www.news.iastate.edu/news/2018/10/15/psychopaths.

- Barbara Kellerman, “How Bad Leadership Happens,” Leader to Leader, 2005, no. 35 (Winter 2005): 33-40, https://doi.org/10.1002/ltl.113.

- Sheehy, Boddy and Murphy, “Corporate law and corporate psychopaths,” 499.

Congratulations on the publication of your articles about Al Dunlap. Your picture of Dunlap on the front cover of Mean Business (1996) reminds one of the wisdom of the saying: “You can’t judge a book by its cover.”

I agree, the more people who know about these people the better for humanity. See also these papers for more details.

BODDY, C. Historical champions of shareholder capitalism: were they corporate psychopaths? The case of Albert Dunlap. The British Academy of Management Annual Conference, 2018. 1-23.

BODDY, C. 2025. Psychopathic Capture within Financial Capitalism: Albert Dunlap, Scott Paper, and Sunbeam Corporation. Journal of Critical Realism in Socio-Economics (JOCRISE), 3, 198-219.