When scientist Dr Jim Bowler discovered ancient Aboriginal remains in remote Lake Mungo he had no idea it would rewrite the history of human occupation in Australia. He also had no idea that taking these bones from the burial sites would cause great distress to the traditional owners of the land.

Man is unable to see himself entirely unrelated to mankind, neither is he able to see mankind unrelated to life, nor life unrelated to the universe.

—Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

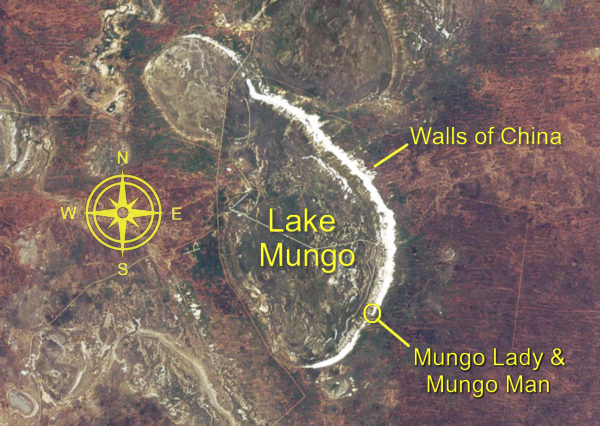

Where is Lake Mungo?

If you go west from Sydney 1371 km you will come to the Willandra Lakes region in the south-western part of New South Wales. But don’t take a boat there because there’s no water in these lake—they’ve been dry for around 15,000 years.

Lake Mungo — Willandra Lakes Region of NSW

Lake Mungo — Willandra Lakes Region of NSWOriginally fed by the Willandra Creek, there are 19 lake beds in this semi-arid region, with Lake Mungo being the second-largest. This system of ancient lakes was formed over the last two million years.

When Europeans first arrived in Australia, the traditional tribal owners were the Mutthi Mutthi people, the Barkandji people, and the Ngiyampaa people. Once the lakes dried, they did not live permanently in the area but used it seasonally and as a meeting place for the three tribal groups.

In the 1850s squatters took over their land for sheep grazing. Over time this proved to be a disaster for both the Aboriginal peoples and the settlers. The tribes were no longer able to continue their traditional hunting and gathering lifestyle but were employed for minimal wages on the station properties. Eventually they were moved to missions and to towns plus many children were rounded up by the Aboriginal Protection Board and placed in foster care with white families.

However, the overstocking of sheep, the introduction of rabbits and severe droughts wreaked havoc on the landscape from wind erosion and from rain.

The drought years of 1943-4 were particularly severe. Keith Newman, reporter for the Sydney Morning Herald, toured the region in December 1944. He experienced dust storms darkening the sky and country where all traces of vegetation “has been eaten out by stock or rabbits.”[1]

In an unmapped area he came across an unnamed dry lakebed:

The local people call It “The Great Wall of China”. This was the greatest of all sandhills I saw in settled country . . . it stretches in a semi-circle around a flat grey depression which must have been a lake in long past days.[2]

Newman also gave a crucial insight into what erosion was doing to Aboriginal burial sites:

Here, and in several other sandhills I saw, erosion is disturbing the dead as well as menacing the living. The wind’s giant hand has scooped away the earth from Aboriginal burying grounds, to reveal the skeletons of long dead men. How long, nobody knows. Such local talk as I could direct to this topic—few are interested—records only one anthropologist having come to this storehouse of ancient lore.

But the anthropologists will have to hurry. I saw one lot of bleached bones, still in recognisable skeleton pattern, which even a layman could see had been buried very long ago. The wind first revealed this skeleton a fortnight back. When I saw it, the bones were already drifting about, and perhaps by now, the wind has scattered the crumbling pieces.[3]

Newman’s entreaty would be ignored for another 20 years. The scientist who would lead the way would be geologist Dr. Jim Bowler.

Who is Jim Bowler?

James Maurice Bowler was born in 1930, the fourth child and only son of James and Alice Bowler of Leongatha, Victoria.

Jim’s father was originally from Ireland, having emigrated to Australia in 1910. In May 1916 the newly married James senior enlisted in the Australian Infantry Forces, served in France and returned to Australia in 1919. Back home in Leongatha he continued life as farmer.

Jim attended the Marist Brothers college in Sale, leaving school at age 15 to continue his education at the Corpus Christi seminary in Werribee. He lasted a year before deciding the priesthood wasn’t for him and returned to Leongatha to grow potatoes for the next 10 years.

Having been on the land for most of his life he decided to go to the University of Melbourne to study geology. He graduated with a Bachelor of Science Honours Degree in December 1958. He continued on with his studies and, by now married to wife Joan, was awarded a Masters degree in 1961. He then lectured in the Geology department before moving with the family to Canberra in 1965 to take up a position as research fellow at the Australian National University (ANU).

As a geomorphologist, his main interest was the study of the nature and history of landforms and relate these to climate change in the Pleistocene Epoch (1.6 million-10,000 years ago). The methods used in Europe to study geomorphology didn’t apply to Australia because the largely flat country did not have the glacial history. Instead Bowler was exploring a different approach by studying the history of water in rivers and lakes for his research.

One of the lake systems he studied was the Willandra Lakes in western New South Wales. These had been suggested to him by his PhD supervisor, geologist Professor Joe Jennings, who had spotted what appeared to ancient lake beds on a flight from Broken Hill to Sydney.[4]

Discovering Mungo Lady

The eastern shoreline of Lake Mango has a distinctive, 30 km long crescent-shaped dune up to 30 metres in height and caused by the prevailing westerly winds. Today this feature is known as the ‘Walls of China’ lunette.

It was in 1967 that he first started exploring the ancient lake bed that he would call Lake Mungo, named after the Mungo sheep station nearby.

Lake Mungo — Satellite Image by Mapbox

Lake Mungo — Satellite Image by MapboxBowler describes his first encounter with the lake:

I set out to explore some of these and to find that in the chain of lakes in the Wallandera area, nature had begun the work of excavating for us. And on the one lake, later to be named Lake Mungo, a huge erosion had really revealed the internal anatomy of the dune. And in the dune landscape there were mussel shells high above the level of the ancient beaches, there was evidence of stone tools, but these were eroded out of their original position, lying on the erosion surface, and there seemed to me to be quite abundant evidence of early human occupation.[5]

Walls of China – Showing stratification and erosion

Walls of China – Showing stratification and erosionOn July 5, 1968 he was in the process of mapping the lake shoreline at the southern end of the Walls of China when he came across what appeared to be bone fragments encrusted in the ancient sediment, at least 20,000 years old. He marked the spot with a stake and on return to Canberra alerted the archaeologists at ANU but there was little interest. Up till 1960 there was the belief that human occupation in Australia went back 5,000 years. During the 1960s the time period was extending but nothing like Bowler was suggesting.

It took until March 1969 before Bowler was able to convince his Canberra colleagues to come to Lake Mungo to take a look for themselves. Archaeologists John Mulvaney and Rhys Jones were among those present. Mulvaney describes what they saw:

He took us to this area and here was this mound that looked like bone and charcoal and he said this was the site I was talking about. And Rhys and I thought, well, this might be human. It was a very dramatic moment. It was more dramatic because there were sheep around and they were walking all over it.[6]

Bowler said Rhys Jones worked “with the skill of a surgeon removing blocks and out dropped a piece of human mandible. That was an extraordinary moment.”[7]

The bone fragments were scooped up and placed in a suitcase to be transported to Canberra and left in the hands of anthropologist Alan Thorne to painstakingly sort through the pieces.

After studying the remains it was concluded that the bones were from a young female that had been cremated and then her skull crushed before being buried in sand. They called her Mungo Lady. Initially the age of the bones was thought to be around 24,000 years.

The discovery of Mungo Lady was incredibly important as the find put Australia on the world stage. But even more staggering was the realisation that this was a ritualised burial. John Mulvaney explained what the finding meant to him:

You don’t bury people with elaborate ritual unless you hold some sort of views about life and death, or after-life. And here among the earliest burials of Homo sapiens in the world we’re seeing people with some kind of philosophy about life and death. And that to me it’s terribly exciting.[8]

It wasn’t long before other archaeologists were busy exploring the Willandra Lakes region. Meanwhile Jim Bowler continued with his research into climate change. In February 1971 he was awarded his PhD for his thesis ‘Late Quaternary Environments: A study of lakes and associated sediments in southeaster Australia.’ [9]

Discovery of Mungo Man

On February 26, 1974 Bowler was on his motorbike weaving his way through the Walls of China looking for extinct marsupial bones when he spotted bone protruding from the sand. This was only 400 metres from where Mungo Lady was discovered. This time a complete skeleton was buried, not cremated, and Alan Thorne, the physical anthropologist found it to be that of an Indigenous male. Again, there was a surprise in what they found, as Bowler recounts:

In scraping away the sand, it became clear that that body had been anointed in ochre from top of the cranium down to the groin. That body was sprinkled or painted with ochre. The ochre had to be traded or brought in from a long distance.[10]

Mungo Man – 1974

Mungo Man – 1974Photo: Professor Bowler – with permission

Initially there were wide estimates on the age of the remains, ranging from 30,000 to 70,000 years. Later tests concluded that both Mungo Lady and Mungo Man were buried between 40,000 and 44,000 years ago.[11]

The finding of these remains had a deep impact on Bowler and others involved:

The critical element here is in the nature of those burials. Immediately it became apparent we were facing the reality of Australians in this landscape long, long before we had imagined. Additionally, the sophisticated nature of their burials was such that these people were highly sophisticated. Fully modern and highly sophisticated culturally.[12]

The Willandra Lakes would prove to be a great place for the archaeologists to find specimens as between 1977 and 1983 some 130 individuals would be removed.[13]

However, there were others who were not happy with what had been going on without their knowledge.

Traditional owners objections

None of the traditional owners of the region were told what had taken place and they were deeply upset when they found out. Mary Pappin, a Mutthi Mutthi elder explained, “Taking the bones away and taking them to the city is taking that person away from their spirit.”[14]

At the time of his discoveries Jim Bowler had never met an Aboriginal person or seen any in the lakes district. “I was totally unaware at that stage, in my ignorance, in my geological ignorance, of any local Aboriginal presence,” he said.[15]

It led to a great deal of tension between the scientists and the Aboriginal people. There were also some mixed reactions among the Aboriginal leaders themselves. Some were appreciative of the scientific work that proved they had such a long history while others said, “We knew this all the time and there was no need to take the remains away.”

The archaeologists couldn’t understand what the fuss was about. Mulvaney admits, “You can say I was more concerned as an archaeologist about archaeological sites than I was about Aboriginal people.”.[16]

Another archaeologist, Dr. William Shawcross, explained their thinking at the time:

We, and that includes me, had not remotely considered that the Aboriginal people would be concerned about what we were doing . . . I suppose I felt rather righteous that here we were rediscovering their past – shouldn’t they be grateful? . . . So it was surprising to be then accosted with, “You’re taking out past from us.” But, of course, there was a distinct truth about that. Our careers, internationally and so, were very much do with the sense we made of somebody else’s past.[17]

These scientists were now becoming world-renowned for their discoveries. While the late Professor John Mulvaney, who died in 2016, is recognised today as the ‘father of Australian archaeology’ and a campaigner for the protection of Indigenous and historic sites and artefacts, he became disillusioned after he was accused of ‘appropriating the past’. He said it was one of the reasons he retired early saying, “I just felt I didn’t want to struggle in a society that said, ‘You’re a villain’.”[18]

The answer was simple and was something the highly highly-respected archaeologist, Isabel McBryde, had been doing for years in her own field work—working with the local Aboriginal people. In his later work in Lake Mungo Jim Bowler had also seen the need collaboration, not just consultation. It was the same in 1978 when he began exploring another lake system in the remote desert lands of north-western Australia.[19]

In 1982 a formal agreement between the scientists and traditional landholders was put in place that in future all work should be done in collaboration with the locals.[20]

World Heritage Listing for Lake Mungo

In 1981 three nominations from the Australian Government were granted World Heritage status by UNESCO. These were the Kakadu National Park, The Great Barrier Reef and the Willandra Lakes Region. John Mulvaney had made the speech to a meeting of the World Heritage committee in Sydney where he recommended “that Mungo should go on a World Heritage list. Now that was really an exciting moment for me personally,” he said after his retirement.[21]

The UNESCO recommendation committee agreed and their report stated:

The Willandra Lakes Region is a remarkable example of a site where the economic life of Homo sapiens can be reconstructed, showing a remarkable adaptation to local resources and a fascinating interaction between human culture and the changing natural environment. The fossil landscape remains largely unmodified since the end of the last Pleistocene ice age.[22]

Unfortunately, and perhaps typically, neither the traditional owners of the tribal lands nor the current land holders were consulted on the proposal and what it would mean for them. They only heard about it after the announcement was made. According to UNESCO documents, two urgent issues remained to be resolved: the legal status of the land and the administration of the heritage site.[23] It was obvious that neither issues had been thought through properly.

Landholders were eventually compensated for the loss of their land. But, such was the distrust of traditional owners, it took another 15 years before the first Plan of Management was put into place in 1996.[24]

These days the traditional owners are very much involved in the administration and tourism aspects of the Mungo National Park.

However, Bowler believes the State and Federal governments are not doing enough, citing the NSW Government decision to disband the Willandra Lakes Region World Heritage Area Community Management Council and the Technical and Scientific Advisory Committee.[25]

The grave robbers

Between 1788 and 1948 thousands of bodies and body parts of Aboriginal people were taken from burial sites around the country and sent to universities and private collectors around the world.

In 1991 Australian journalist and researcher David Monaghan disclosed the extent of the plundering:

British and Australian scientists ran one of the biggest grave-robbing networks ever organised. Studies by an Australian academic researching in Oxford indicate the graves of between 5,000 and 10,000 Australian Aborigines were desecrated, their bodies dismembered or parts stolen to support a scientific trade.[26]

One of interests in Britain during the first half of the nineteenth century was the pseudo-science of phrenology. The belief at that time was that the bumps in the cranial bone could relate to specific faculties of cognition, affect, emotion or reasoning.[27]. Edinburgh became the centre for these followers and gathered a huge collection of skulls and death masks.

Prior to 1860, it is estimated there were around a hundred remains of Indigenous Australians in British natural history collections.[28] After Charles Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, was published—together with his prediction of the extinction of this ‘inferior race’[29]—demand for bodies, and especially heads, grew exponentially.

One of Darwin’s contemporaries, Thomas Henry Huxley, was convinced that Aboriginal skulls clearly showed there was little advancement from Neanderthals.[30] The result was a rush by museums and anatomy schools to acquire these ‘living fossils’.[31]

This ‘gold rush’ continued well into the twentieth century.

The 1910 edition of the guide for visitors to the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons in London proudly boasted its collection:

Case 3 [is] where one of the largest and best collections of the skulls and skeletons of Australian Aborigines is preserved. Anthropologists are now generally agreed that in this race, and also in the Tasmanians shown in the next case, we have the most primitive of all existing forms of Mankind. They have certain points in common with those most ancient inhabitants of Europe – the Neanderthal race.[32]

The Tasmanian Aboriginal people were highly prized specimens because they were being hunted and killed during the 1800s and their numbers were reducing. They were seen by many settlers as an inferior race and as vermin to be exterminated. From the original population in 1803 of around 6,000 when White settlement took place, the number of Tasmanian Aboriginal survivors was reduced to 135 by 1830.[33]

Australian institutions also got into the business during the second-half of the nineteenth century with the major collections being in the Sydney, Melbourne and Adelaide museums and universities.

By far the most prolific collector of some 1800 Aboriginal remains was Murray Black, a farmer who, later in life, was also an amateur anthropologist.[34]

George Murray Black was born in 1874 at Tarwin Meadows in Gippsland, Victoria. He trained as a civil engineer at the University of Melbourne before taking over the family farm upon the death of his father in 1902. [35]

Cultural historian Paul Turnbull notes, “Black plundered numerous traditional burial places, mostly along the Murray River, from the late 1920s until well into the 1950s.”[36]

Jim Bowler interviewed Murry Black not long before his death in 1965. Black told of his bone collecting activities for the Australian Institute of Anatomy in Canberra and later for Anatomy Department of the University of Melbourne. One of his sources was the Kow Swamp in northern Victoria which would later become famous for the finding of ancient Aboriginal remains by Allan Thorne from the ANU.

Bowler wasn’t impressed with what Black and others had been doing:

That whole process that he [Black] was involved in . . . comparing Neanderthals that had already been found in Europe with Aboriginal skulls. There was already a huge collection of skulls in England. Then the physical anatomists just followed that up and it became almost an unholy competition. Cranial profiling.[37]

In a reflective piece Bowler wrote in 1995, he is not proud of what he and others did in the name of science:

In the absence of an attempt to understand the continuity between past and present Aboriginal cultures, `scientific research’ was simply grave-robbing. In the eyes of the disempowered remnants of the indigenous occupants, it was sacrilege. Their sense of deep indignation, of institutionalised oppression and exploitation, cannot easily be absolved by modern compromise. The wounds are many and deep; the scars will take a long time to heal.[38]

Repatriation of Aboriginal remains

A long-time festering issue with Aboriginal people has been for the return of remains of their ancestors. They strongly believe that the spirits of the dead cannot rest until returned to their ‘Country’. As Kate Galloway writes, “This is not very different from the beliefs that cause us [Caucasians] to expend so much effort to repatriate military personnel.”[39]

Aboriginal people had known for 150 years about the desecrations of graves taking place but were powerless to do anything. Aboriginal lawyer and activist Michael Mansell describes growing up in Tasmania in the 1950s and ‘60s:

We never ever questioned the right of any white person, whether they had a blue uniform or not, to come into our homeland more or less to do what they liked. That was just part of life and I grew up and people of my generation grew up in an environment where we had no rights other than the rights within our community. [40]

This situation would change from the 1970s whereby Aboriginal people were demanding ownership of the past and a greater say on what research was done and its interpretation. [41]

One of the leading figures in the repatriation of Aboriginal remains has been Michael Mansell. As the legal director for the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC) the campaign for the return of remains has been going on since 1985. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC) was also heavily involved until it was abolished in 2004. Since 1992 the Australian Government has supported the repatriation of Australian Indigenous ancestral remains from overseas and as at October 2017, 1475 remains have been returned.[42]

The process has been painfully slow because many institutions want to maintain their collections and, in many jurisdictions, local laws prevent their return. Another difficulty has been due to many remains having no indication of their origin recorded so it is impossible to rebury them in their ‘country’.

One of the proposals that Jim Bowler and John Mulvaney had been pushing for many years was for establishing a ‘Resting Place’ for such remains. A 2014 consultative committee recommended the urgent establishment of a National Resting Place but so far there has been no action taken by the Australian Government.[43]

Many heritage professionals and archaeologists didn’t agree with the repatriation push. One reason given was that new technologies, as they become available, enable the discovery of more information about these ancestors.

John Mulvaney, for one, maintained that ancient remains were the common heritage of humanity.[44] In 2006 he made clear his opposition to repatriation when he stated, “I simply do not accept that the remote past can be ‘owned’ by a local clan.”[45]

Return of Mungo Lady and Mungo Man

After lengthy and sometimes heated discussions between Aboriginal people and archaeologists, Alan Thorne offered to return Mungo Lady. On 11 January 1992, a moving ceremony took place at the Walls of China in Lake Mungo, with Thorne handing over the remains to thirteen elders, and witnessed by around 200 people from the three Aboriginal communities. In the end they decided to preserve the remains in a secure, hidden vault instead of burying the bones.

Jim Bowler also agitated for years for the return of Mungo Man to the traditional owners:

I realise that when we took those bones away there was a lot of hurt amongst Aboriginal people – here go the scientists – here they go again inflicting injury on our dead. So for that I think we owe an apology, for what science has done to the Aboriginal people in the past especially for the abuse of human remains.[46]

Bowler used every opportunity to push for their return and finally, after four decades, it did happen.

On November 6, 2014 the Australian National University handed back the remains of Mungo Man and 140 others taken from the Willandra Lakes area. Before they would be transported back to Lake Mungo the remains were stored at the National Museum of Australia in Canberra.

The final homecoming took place in Lake Mungo on November 17, 2017, a very emotional day for all those present, including Jim Bowler.

Jim Bowler on Change

The finding of Mungo Lady and Mungo Man has had a profound effect on Jim Bowler, so much so it would change his life.

He was initially in awe when he first observed evidence of human habitation in the Walls of China at Lake Mungo which he thought went back 20,000 years. He said later, “I found myself walking in the footsteps of people in the past. I found stone tools. I found freshwater shells. Evidence that people had been there at great antiquity in the past.”[47]

When Mungo Lady was discovered it showed, according to Bowler, “the first record of a degree of cultural sophistication, previously quite unimagined.”[48]

For Bowler, and others present, this was an extraordinary moment:

And I suppose it’s that moment and the subsequent discovery of Mungo Man and his excavation that have stayed with me and really, I think, the responsibility now is to translate those moments into the intellectual framework of Australians today. That, as I see now, is a great challenge.[49]

He believes that Australians are yet to appreciate that the Australian landscape has been humanised for tens of thousands of years.[50]

It was only after his discovery of Mungo Lady that he met Aboriginal people for the first time. By engaging with the traditional owners, Bowler experienced a gradual appreciation and admiration for their culture and worldviews:

The opportunity to enter into dialogue with the Aboriginal people opened an entirely new window on to my understanding of their culture, their reverence for nature, and their innate sense of the sacred. The Mungo people had a deep consideration for the sanctity of life, for its continuation after death, that has certain similarities with my own Christian heritage. For Indigenous Australians today, the Earth is something sacred. When they speak about the landscape, the waterholes—created by their ancestors—they speak about the presence of the sacred. This notion that the natural world is something sacred is a sensitivity that our modern society has to rediscover.[51]

Another important realisation that Jim Bowler has come to is what he refers to as ‘the bloody Enlightenment’. In considering the dispossession of the Aboriginal people since the First Fleet arrived in 1788, he sees the problem with Enlightenment today in this way:

Prepared by Descartes, nurtured by the great advances of Newton in the context of Judaeo-Christian notions of conquest of the earth, the grand synthesis of Charles Darwin served multiple purposes. It entrenched earlier conservative attitudes, and created and justified new ones. It emphasised the idea that there was a dichotomy between science and nature. The superiority of the white races seemed at last to be underpinned by scientific justification, and the gap between western `civilised’ people and the barbaric races of the earth was absolute.[52]

He sees the clash of the Aboriginal descendants of Mungo Lady and Mungo Man and the archaeologists as a conflict between modernity and intuition. He concludes that “the purely rational mind is incapable of understanding what Aboriginal people are fundamentally on about.”[53]

Bowler has spent more than 50 years in investigating climate changes over thousands of years. Change is always with us. We are either agents of change or products of change.

Although he has used the scientific method for most of his life, he is convinced the rational, mechanical view of nature is no longer adequate:

The mechanistic view of reality is alive and prospering. It is enshrined in our economic systems, institutionalised in major corporations in which the profit motive is driven by the ordained precepts of progress and development. The price of such innovation is now evident in the enormous damage the human race has visited on the fragile resources of the planet – damage that has arisen directly from explosive populations empowered by expanding technologies, but with little awareness of their long-term impact. [54]

The scientific method, being based on the principle that the observer is assumed to be disinterested and detached from the object being observed, needs to be extended to take an interest in the object being observed.

This links to another deveopment Bowler wants to see: that of mutual understanding of the Aboriginal and Western cultures:

Unless there is a real sense of mutual learning and empathy between the competing cultures, the current agenda of reconciliation will remain little more than a political apologia. . . The challenge we face today is not only to accommodate Aboriginal aspirations but also to become more aware of their own living landscape and their sense of place in it. . . As a largely European culture, now sharing a continent with a people who had at least 60,000 years of continuous occupation, we have an extraordinary opportunity to produce a synthesis of the old and the new, of the material and spiritual, of humanity and nature. The key to that synthesis involves opening our minds to mythologies and cultures that remain alive in Australia as in no other place on earth.[55]

Inspired by the message of Mungo Man, James Maurice Bowler won’t rest until he sees these changes come about.

Notes

- Keith Newman, “An Artist’s Journey Into Australia’s ‘Lost World’,” Sydney Morning Herald, December 16, 1944, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/page/1085643.

- Newman, “An Artist’s Journey”.

- Newman, “An Artist’s Journey”.

- Billy Griffiths, Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia (Carlton VIC, Australia: Black Inc., 2018) Ch. 5. Kindle ebook.

- Robyn Williams, “How Old is Mungo?,” The Science Show, aired April 12, 2003 (Sydney: ABC Radio National), radio program transcript, http://www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/scienceshow/how-old-is-mungo/3540898#transcript.

- Andrew Pike, “Message from Mungo,” Ronin Films 2014, aired July 29, 2017, SBS On Demand, https://www.sbs.com.au/ondemand/video/498456643653/message-from-mungo.

- Williams, “How Old is Mungo?”

- Pike, “Message from Mungo”.

- James M. Bowler, “Late Quaternary Environments: A study of lakes and associated sediments in southeaster Australia,” (PhD thesis, Australian National University, 1970), http://hdl.handle.net/1885/138876.

- 1GOD.com, Professor Jim Bowler- Sacred Australia, online video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_OL413j6Hok.

- Jim Bowler, “Science focus: Putting flesh on old bones: archaeology and Australia today,” in Science Focus 4, ed. Kerry Whalley (Melbourne: Pearson Education Australia), 255-59.

- 1GOD.com, Professor Jim Bowler.

- Lisa McGregor, “Long Journey Home,” Australian Story, screened February 12, 2018 (Sydney, NSW: ABC TV, 2018), Television Broadcast transcript, http://www.abc.net.au/austory/long-journey-home/9424588.

- McGregor, “Long Journey Home”.

- McGregor, “Long Journey Home”.

- Pike, “Message from Mungo”.

- Pike, “Message from Mungo”.

- Pike, “Message from Mungo”.

- Mary V. Cass, “Learning from Australia’s first migrants,” Kairos 24,7 (April 28, 2013): 20, 7, http://www.cam.org.au/Portals/0/kairos/kairos_v24i07/index.html.

- McGregor, “Long Journey Home”.

- Pike, “Message from Mungo”.

- Jeffrey McNeely, World Heritage Nomination: IUCN Technical Review 167 Willandra Lakes Region, IUCN/CNPPA, February 19, 1982, http://whc.unesco.org/document/152886.

- McNeely, World Heritage Nomination.

- Harvey Johnston and Richard Mintern, “Managing Australia’s World Heritage in the Willandra Lakes Region,” in Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia, ed. Penelope Figgis (Sydney: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc.), 102-7, http://aciucn.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/19_Mintern.pdf.

- Jim Bowler, “Mungo Man returns home,” Yingadi Aboriginal Corporation, http://www.yingadi.org.au/index.php/resources/download/2-general/17-mingo-man.

- David Monaghan, “Angel of Black Death,” Australian Bulletin, November 12, 1991, 30-38.

- Paul Turnbull, Science, Museums and Collecting the Indigenous Dead in Colonial Australia (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 153.

- Turnbull, Science, Museums and Collecting, 96.

- Jerry Bergman, The Darwin Effect (Green Forest, Arkansas: Master Books, 2014), Ch. 6. Kindle eBook.

- Turnbull, Science, Museums and Collecting, 138.

- Turnbull, Science, Museums and Collecting, 139.

- Arthur Keith, Illustrated Guide to the Museum of The Royal College of Surgeons, England (London: Taylor and Francis, 1910), 31, https://ia802706.us.archive.org/2/items/b21463384/b21463384.pdf.

- Rebecca Kippen, “The population history of Tasmania to Federation”, Australian Population Association, https://www.apa.org.au/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Wed%20Plen%201100%20Kippen.pdf.

- Turnbull, Science, Museums and Collecting, 352.

- Sarah Robertson, “Sources of bias in the Murray Black collection: implications for palaeopathological analysis,” The Free Library, https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Sources+of+bias+in+the+Murray+Black+collection%3a+implications+for…-a0169134508.

- Turnbull, Science, Museums and Collecting, 352.

- Paul Daley, “Finding Mungo Man: the moment Australia’s story suddenly changed,” The Guardian, November 16, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2017/nov/14/finding-mungo-man-the-moment-australias-story-suddenly-changed.

- Jim Bowler, “Reading the Australian Landscape: European and Aboriginal Perspectives,” Cappuccino Papers 1 (1995), 9–14, https://web.archive.org/web/20150227003001/http://www.ecoversity.org.au/publications/bowler1995.htm.

- Kate Galloway, “Legal grey area hinders Aboriginal repatriation,” Eureka Street, June 16, 2016, https://www.eurekastreet.com.au/article.aspx?aeid=49537.

- Michael Lavarch, “Bringing them home: Report of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families,” (April 1997), Australian Human Rights Commission, https://www.humanrights.gov.au/sites/default/files/content/pdf/social_justice/bringing_them_home_report.pdf.

- Claudio Tuniz, Richard Gillespie and Cheryl Jones, The Bone Readers: Atoms, genes and the politics of Australia’s deep past (Crows Nest NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2009), 41.

- Department of Communications and the Arts, Indigenous Repatriation Program International (Canberra: Australian Government, 2017), https://www.arts.gov.au/file/5086/download?token=2KfA6TrW.

- Advisory Committee for Indigenous Repatriation, National Resting Place Consultation Report 2014 (Canberra: Australian Government, 2015), https://www.arts.gov.au/file/1081/download?token=iyE_3QVI.

- Tuniz, The Bone Readers, 206.

- John Mulvaney, “Reflections,” Antiquity, 80, 308 (Jun 2006): 425, ProQuest Central.

- McGregor, “Long Journey Home”.

- David Murray, “The Death and Afterlife of Mungo Man.” Beyond the Lab, aired November 21, 2015 (Sydney: ABC Local Radio), Radio broadcast, http://www.abc.net.au/local/programs/438-beyond-the-lab/episodes/ep-2015-11-21-4356610.htm.

- Anna Henderson and Peta Donald, “Australian National University offers apology to elders as Mungo Man remains handed back to traditional owners,” ABC New, Melbourne, November 6, 2015, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-11-06/anu-apologises-as-mungo-man-returned-to-traditional-owners/6919712.

- Williams, “How Old is Mungo?”

- Cass, “Learning from Australia’s first migrants”.

- Cass, “Learning from Australia’s first migrants”.

- Bowler, “Reading the Australian Landscape”.

- Daley, “Finding Mungo Man”.

- Bowler, “Reading the Australian Landscape”.

- Bowler, “Reading the Australian Landscape”.