When Frank Serpico saw what was inside the envelope he had just been given, he knew immediately he was facing the crisis of his life. Here he was, a police officer just six months into his plainclothes assignment, being handed $300 from another policeman—a payment from an illegal gambler for police protection.

Ten percent of the cops in New York City are absolutely corrupt, ten percent are absolutely honest, and the other eighty percent—they wish they were honest.

– Frank Serpico, New York City police officer, 1959–1972

Up to this point Serpico had not said a word to anyone about the wide-spread corruption he had observed in the plainclothes division. He told other police officers he wasn’t interested in what they did but he wasn’t going to take part. He just wanted to get on with the job of catching crooks and serving the community. Now that he had received the envelope he would also be tainted if he was found with this money and it would likely be the end of his career. Becoming a policeman was something he had yearned for since he was a kid.

He had to report it, but to whom? He knew he couldn’t approach his immediate superiors because they were part of the scheme.

Frank Serpico’s Upbringing

Francesco Vincent Serpico was born on April 14, 1936 in Brooklyn, New York, the youngest of four children of Vincenzo and Maria Serpico. His parents were immigrants from Marigliano in Southern Italy, who had arrived in the United Stated almost a decade earlier.

His father was a shoemaker who took great pride in his work as a craftsman. As a 13-year old, Frank would be seen on a Sunday morning after church shining shoes in his father’s shop. From his hard-working parents Frank was exposed to a world of independent spirit, frugality, integrity and self-respect. These characteristics would remain with him for the rest of his life.

The family prospered and for his school holidays in the summer of 1949 he spent time with family members back in Italy. As a young boy he was particularly impressed with the way his uncle, a member of the carabinieri—Italy’s national policeforce—went about his plainclothes duties and the respect he had from the community:

I just marveled at the respect and dignity with which he did his work, and how people respected him.[1]

Back home he had observed both good cops and brutal cops. Generally, there was little respect by the public for its members but, from the time he was a child, he had wanted to join the New York Police Department. He would have to wait a few years as applicants needed to be 20 years old.

Instead of waiting to be called up for military service, in 1954 Frank enlisted in the US Army and spent two years in South Korea.

Upon returning to civilian life he enrolled in Brooklyn College while working as a part-time private investigator and as a youth counsellor.

Frank Serpico – NYPD Patrolman

Frank sat for the entrance exam to the Police Academy and was accepted to start on September 11, 1959. Six months later he graduated as a patrolman.

The City of New York Police Department is divided into 77 precincts or patrol areas, spread out through the five administrative boroughs of the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, and Staten Island. Frank was assigned for duty at the 81st Precinct in Brooklyn, an area with a high crime rate at that time.

On his very first day he was introduced to the way his fellow police officers went to local cafes for their free lunch. After a while Serpico refused to be part of it and paid for his meals; he could tell that the café owners resented the practice and he felt that police on the take lost respect of the public. He didn’t realise that this was nothing to what he would be exposed to in his years to come:

I wasn’t naive when I entered the force as a rookie patrolman . . . I knew that some cops took traffic money, but I had no idea of the institutionalized graft, corruption and nepotism that existed and was condoned.[2]

Serpico was soon exposed to the practice of police sleeping while on duty, known as “cooping,” with the full knowledge of the sergeant in charge. And then he witnessed a driver giving a policeman a $35 bribe to avoid a ticket for going through a red traffic light. He refused to take half, which was meant to be his share of the money. He soon realised these were both the accepted and the expected ways for police to behave when on patrol duty.

After a two-year stint at the 81st, Serpico was transferred to the Bureau of Criminal Identification. The BCI was primarily a record-keeping operation but it was also meant to be a stepping stone to become a detective. This didn’t happen after he “crossed swords” with the BCI inspector and early in 1965 Serpico found himself being transferred to uniformed duty in the 70th Precinct in a middle-class area of Brooklyn.

Plainclothes had a reputation for graft and corruption which Serpico observed but ignored. By this time Serpico had been living in Greenwich Village, complete with a bushy beard, and had adopted the look of a hippy rather than a police officer. This caused some ructions with many of his superiors and fellow police officers with a minority supporting his ability to disguise his true calling when working out of uniform.

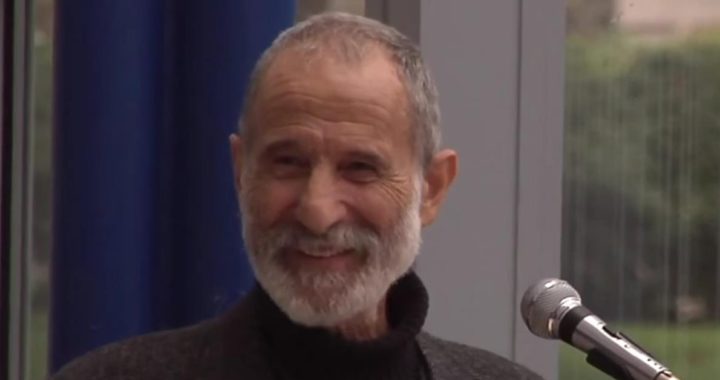

NYPD Patrolman Frank Serpico

NYPD Patrolman Frank SerpicoSerpico was determined to become a detective and his supportive boss, Captain Fink, submitted a recommendation for a plainclothes assignment. On January 1966, Serpico commenced the Criminal Investigation Course at plainclothes school and upon completion he was sent back to Brooklyn to join the 90th Precinct plainclothes squad. The neighbourhood ranged from middle-class to poor with the main concerns being drugs and illegal gambling.

Serpico relished the job and preferred to work on his own. He was successful in arrests of illegal gamblers in particular.

By the middle of 1966 he realised that others were wary of him for not being part of the team and for being too ‘keen’ on the job. Then, a month later, in August, the Captain issued a trumped-up charge that Serpico had deserted his post. It would have meant Serpico being transferred to uniformed work with no chance of becoming a detective. Fortunately, Serpico’s appeal to the inspector in charge quashed the charge but it was a warning to Serpico that he did not fit the mold of being a compliant team player.

A few days later it happened; the envelope with $300 inside was thrust into Serpico’s hand.

Serpico Discovers a Corrupt Police Department

It was while Serpico was on the Criminal Investigation Course that he had met David Durk, a junior policemen who also abhorred corruption. Durk’s background was very different to most policemen. He was the son of a doctor; he was a political science graduate from the prestigious and highly selective Amherst College in Massachusetts; and had studied law at Columbia University before joining the police force. At that time, he was on secondment to the Mayor’s office. It was obvious to Serpico that Durk has highly ambitious but had many useful high-level contacts both inside and outside the NYPD.

Since Serpico didn’t know anyone he could go to, he called Durk to ask what he should do about the envelope he had received that day. They met up the next day and Durk proposed they both meet with Durk’s immediate boss, Captain Philip Foran, an officer in the Chief Inspector’s Investigating Unit.

Serpico went along with the idea but was somewhat suspicious because he knew Foran had previously been a plainclothes policeman, and they were known for being corrupt.

When the meeting took place, Serpico couldn’t believe what he heard. Foran suggested two options. One was to keep going with Serpico’s complaint adding, “By the time it’s all over, they’ll find you face down in the East River.” The other was to forget the whole thing.[3]

This set the pattern that was to follow over the course of the next year with each of the contacts Durk came up with. No one was interested in seriously tackling the issue that police command were turning a blind eye to the systemic corruption throughout the NYPD.

In November 1966, three months after receiving the envelope, Serpico was transferred to another plainclothes group. This time it was the 7th Division in the Bronx, covering four precincts. Told beforehand that the 7th was ‘clean as a hound’s tooth’, he soon found out it was the worst place for graft and corruption he had come across. And it was blatant. One cop, Robert Stanard, told him he had made $60,000 in the previous two years from the ‘pad’, the payoff system from illegal gamblers.

This time he tried a different tack by contacting Captain Cornelius Behan, an officer he previously worked for. Behan was sympathetic to the situation Serpico was in and promised to introduce him to the number-two man, the First Deputy Commissioner John Walsh, for an investigation to take place. Walsh’s response was that Serpico should remain in the 7th Division and collect incriminating evidence—an extremely dangerous task when surrounded by suspicious cops who wouldn’t have anything to do with him. Walsh promised to keep in touch but completely ignored him.

By October 1967 Serpico’s position was becoming untenable. He was doing his job and arresting individuals for illegal gambling when they were paying his colleagues for protection. He hadn’t heard from Walsh and told Behan he was going to approach outside agencies. This was something the NYPD didn’t want and within days he was talking to senior officers about an investigation into his complaints.

A low-level investigation of police by police command wasn’t what Serpico wanted and he was reluctant to take part. He knew that all it would do would be to implicate the police on the front line and ignore the upper levels of the organisation—captains, deputy inspectors, inspectors and assistant chiefs and above. In the end he relented and gave details of thirty-six locations where payoffs to police were occurring.

The investigation limped on for several months without much result until a raid in March 1968 on a betting establishment confirmed what Serpico had been saying. The operators named the policemen they were paying off and with that it was all the investigation wanted. The police command could then say they had routed out corruption.

Serpico Testifies

The State of New York requires a grand jury as the first step in proceedings against alleged offences such as the police investigation uncovered. The purpose of a grand jury is for a jury of citizens to decide if there is enough evidence to justify the filing of criminal charges. It is held in secret and defendants are not present, except if they appear as witnesses.

The Bronx district attorney took on the case in May 1968 and from late June Serpico, sans beard, was the main witness. Meanwhile the police at the 7th Division who knew they may be called to give testimony were deeply worried and were especially suspicious of Serpico’s role in the investigation. Robert Stanard was one of policemen in the 7th who warned Serpico not to ‘rat’ on his fellow officers.

In November 1968, Stanard appeared before the jury as one of the last witnesses and no longer bragged about making $60,000 for himself but flatly denied any knowledge of the existence of any such ‘pad’.

Even though the grand jury had the power to investigate further in the organisation, Serpico was disappointed that only low-level police were indicted and sent for trial. By then it had been leaked that Serpico was the source of most of the evidence provided to the grand jury. His life was now in grave danger even though he had been transferred from the 7th Division to plainclothes duty in Manhattan North.

It was here that he met with Inspector Paul Delise, the new commander of Manhattan North. Known to others derisively as ‘Saint Paul’, Delise had a reputation for honesty. As they worked together during 1969 there was mutual respect between them.

Serpico has still hurting that the grand jury had not investigated the complicity of police command in the graft and corruption taking place. David Durk had been suggesting they go his contact at The New York Times to tell the full story. Serpico felt the Times wouldn’t listen to two low-level cops, but they might take notice if an Inspector backed up their story. Delise understood very well that being involved could ruin his career but in the end decided to go along with it. It was a brave and critical decision.

Serpico the Whistleblower

According to the Government Accountability Project, a whistleblower is:

An employee who discloses information that s/he reasonably believes is evidence of illegality, gross waste or fraud, mismanagement, abuse of power, general wrongdoing, or a substantial and specific danger to public health and safety.[4]

There are two approaches a whistleblower can take when divulging wrongdoing: internally through the organisation’s internal ‘anti-corruption’ body or externally through regulators, the police or the media.

Anyone who has been a whistleblower will go through a life-changing experience. They are likely to find themselves isolated, demoted, fired, experience mental and physical problems, and divorced. Serpico wasn’t married at the time but he was in a relationship.

In Serpico’s case, he had evidence of illegal activity of graft, corruption at lower levels in the NYPD. It was obvious to him that the police work in many cases was directed to making money for themselves which meant less time for solving crimes. This was a risk to the health and safety of the community, plus it meant the community had little respect for police in general. All he wanted to do was to change the organisation culture such that bad cops would be frightened of good cops instead of the other way round.

Serpico had found the internal anti-corruption bodies as well as external bodies were not effective in bringing about change.

He therefore had no qualms about going to the media.

Serpico’s disclosure to The New York Times

David Durk’s contact at The New York Times was an experienced reporter, David Burnham, who covered law enforcement and the justice system. When Serpico, Durk and Delise met with Burnham on February 12, 1970 Burnham knew from his own reporting that things were not as they should be with the NYPD. But these revelations astounded him and editors at the Times. This would become one of the biggest stories of the year but had to wait for the right time to release it. Burnham engineered the trigger himself by alerting Mayor John Lindsay’s office that the Times was preparing a major story on corruption within New York’s Police Department.

The warning sparked immediate action from the Mayor’s office. After consulting with the Police Commissioner, the Mayor announced on April 23 that a committee would examine “procedures . . . for investigating possible corruption in the Police Department.” This announcement was meant to beat the Times to the story and show they were on top of the problem.

In fact, they were totally unprepared for the impact the lead article would have when it was published two days later under the headline, ‘Graft Paid to Police Here Said to Run Into Millions’, with the introduction:

Narcotics dealers, gamblers and businessmen make illicit payments of millions of dollars a year to the policemen of New York, according to policemen, law‐enforcement experts and New Yorkers who make such payments themselves.

Despite such widespread corruption, officials in both the Lindsay administration and the Police Department have failed to investigate a number of cases of corruption brought to their attention, sources within the department say.

This picture has emerged from a six‐month survey of police corruption by The New York Times.

The picture also is drawn from interviews with a group of policemen — including several commanding officers — who decided to talk to The Times about the problem of corruption because, they charged, city officials had been remiss in investigating corruption.

The names of the policemen who discussed corruption with The Times are being withheld to protect them from possible reprisals.[5]

The story was a sensation and was picked up by other media outlets—print, radio and TV—around the country.

The Police Commissioner, Howard Leary, who was one of the members of Mayor Lindsay’s committee, didn’t inspire confidence in its outcome when he claimed the Times disclosure was a smear campaign by “disgruntled policemen.” Leary would resign four months later.

On May 21, a humbled Mayor Lindsay announced the scrapping of his committee and the appointment of Whitman Knapp, a respected lawyer, to head up what would become known as the Knapp Commission. Its charter was to investigate fully the accusations of police corruption.

Serpico Testifies at Perjury Trial

Shortly after, the criminal case of perjury committed during the 1968 Grand Jury by 7th District policeman, Robert Stanard was underway. As Serpico was the main witness for the prosecution he would soon be identified in press reports on the proceedings. The day after Serpico appeared as a witness, full details of his name and testimony appeared in the June 19 edition of The New York Times.[6] To many in the public he was a hero. To others, especially the police, he was officially a ‘rat’.

On June 30, 1970 Stanard was found guilty of perjury and sentenced to serve one-to-three years jail. He was paroled after serving eighteen months and then won an appeal for wrongful conviction. At his second trial in 1974 the jury found him guilty again.[7]

This was just one of several trials or dismissals of New York police during the early 1970s as a result of the Grand Jury inquiry.[8]

Serpico is Shot

Detective Third-Grade Frank Serpico took up his assignment in Narcotics, Brooklyn South in mid-1970 after the first Stanard trial was over. He was a marked man and not trusted by his fellow team members. Surprisingly, given Serpico’s known stance on corruption, he was approached by a Narcotics detective and offered ‘easy money’—not just hundreds of dollars a month, but many thousands of dollars. This money came from grabbing the takings from heroin dealers, who could hardly complain they were robbed by police. Everywhere Serpico went, corruption was staring him in the face.

On the night of February 3, 1971, Serpico was part of a drug raid at an apartment building in South Williamsburg, Brooklyn. As he spoke Spanish, he was to say he wanted to do a buy and get the dealer to open the door. The other detectives were then to enter the apartment.

The dealer did open the door partly but Serpico was pinned between the door and the doorframe. Recently, Serpico spoke about how he came to be shot and how his partners let him down:

I made the mistake to take my eye off the [perpetrator], to say to my partners, what the hell are you waiting for, give me a hand. When I turned back, boom, that was it, I got shot in the face.[9]

While Serpico lay bleeding on the floor, the other policemen were of little help. It was an elderly Hispanic man who lived in the apartment block who rang for assistance.

Another police car arrived and rushed Serpico to the Greenpoint Hospital, less than two miles away. Once Serpico was in the emergency room, the hospital staff set about finding out the state of his injuries. His face was no a pretty sight; X-rays revealed the .22-caibre bullet had entered the left-hand side of face close to his nostril and broken up with a major fragment lodging in the bone of his left ear. The main concern was a tear to the cerebral membrane and possible infection of the brain. Remarkably, the bullet had just missed his carotid artery, had not entered his brain and had not shattered his jawbone. His recovery was also remarkable. After six weeks in hospital he was discharged with the bullet fragments still in his head. The main long-term outcome was the permanent loss of hearing in his left ear.

Not everyone was pleased to see him recovering. While still convalescing in hospital he received a get-well card with the words, “With sincere sympathy—that you didn’t get your brains blown out you rat bastard. Happy relapse.”[10]

Knapp Commission Hearings

Serpico was sufficiently recovered from his injuries to be able to give testimony at the Knapp Commission hearings in October and December 1971.

As well as answering questions from chief counsel to the commission, Serpico made a statement, beginning with:

Through my appearances here today I hope that police officers in the future will not experience the same frustration and anxiety that I was subjected to for the past five years at the hands of my superiors because of my attempt to report corruption.

I was made to feel that I had burdened them with an unwanted task. The problem is that the atmosphere does not yet exist in which an honest police officer can act without fear of ridicule or reprisal from fellow officers.

We must create an atmosphere in which the dishonest officer fears the honest one and not the other way around. I hope that this investigation and any future ones will deal with corruption at all levels within the department and not limit themselves to cases involving individual patrolmen.[11]

Serpico wasn’t the only policemen to testify or assist the Commission. Four corrupt police offers were induced to cooperate and other honest police also assisted the investigation, backing up Serpico’s story.

After two-and-a-half years of investigation, the final report of the Knapp Commision was released on December 26, 1972.

Even though the Commission had a restricted mandate, few investigative resources, legal restraints, a limited budget, and a short time available to complete the job, the disclosure of the level of corruption was staggering in two ways. Firstly, the shear number of police officers involved in the ‘take’—suggested to be more than half of the 32,000 members of NYPD. Secondly, there was a wide range of situations where corruption would be found, including payoffs from gambling, narcotics, prostitution, construction sites—in fact wherever laws needed to be enforced.

The commission found there were two categories of corrupt police, “meat-eaters” and “grass-eaters”. Meat-eaters are those policemen who aggressively misuse their police powers for personal gain, while grass-eaters simply accept the payoffs that the come their way, as with the envelope that Serpico was given. Relatively few police members are meat-eaters but they can earn huge sums of money from their activities, knowing full well they will be protected by the many grass-eaters who, because they are also involved to a degree, won’t report them.[12]

Aftermath of Knapp Commission

Investigators for the commission uncovered a number of instances of corruption which were passed on to a Special Force set up to look into 310 cases involving 627 police officers. At the time the report was released, twenty-six police officers had been indicted, with a further twenty-three yet to come to trial.

Serpico was disappointed the Knapp Commission wasn’t able to expose the problem at senior levels of the organisation but Murphy, the new Police Commission, was making some changes in departmental procedures for dealing with corruption. He was also relieving twenty-five senior personnel of their commands. Many doubted this would be enough.

Would this be the end of corruption in NYPD? No, just 20 years after Serpico brought forward evidence of corruption, another inquiry was called for. Released in 1994, the Mollen Report detailed a new form of corruption by NYPD officers:

While the systemic and institutionalized bribery schemes that plagued the Department a generation ago no longer exist, a new and often more invidious form of corruption has infected parts of this City, especially in high-crime precincts with an active narcotics trade. Its most prevalent form is not police taking money to accommodate criminals by closing their eyes to illegal activities such as bookmaking, as was the case twenty years ago, but police acting as criminals, especially in connection with the drug trade.[13]

What hadn’t changed, according to the report, is the culture that prizes loyalty over integrity whereby honest officers fear the consequences of “ratting” on cops committing crimes. And then there are the supervisors who choose to ignore corruption and a department that ignores its responsibility to ensure the integrity of its members.[14]ibid p.1]

What happened to Frank Serpico?

In May 1972, Serpico was awarded NYPD’s highest honour, the Medal of Honor. A month later, on June 15, 1972 he retired on a disability pension and moved to Switzerland to recuperate. After spending almost a decade living in Europe he returned to the United States.

Serpico’s story was the subject of the best-selling book by Peter Maas, followed by the 1973 movie, Serpico, starring Al Pacino.

Serpico continues as an activist, speaking out against police corruption and brutality, lecturing to students at universities and serving as a mentor to officers in situations similar to what he endured.

Professor Francis Petit, Associate Dean for Executive Programs at Fordham University, says Frank Serpio’s story shows we need to cultivate principled leaders to counteract those with power and influence who are involved in corruption, greed and scandal:

“Frank Serpico is a person who remained true to his moral convictions even in a very difficult, dangerous and tumultuous environment. All individuals, including executives, can learn a great deal from the journey Frank Serpico traveled as a New York City police officer.”[15]

Notes

- Frank Serpico, “The Police Are Still Out of Control, I Should Know,” Politico Magazine, Oct 23, 2014, https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/10/the-police-are-still-out-of-control-112160 .

- Serpico, “The Police Are Still Out of Control”.

- Peter Maas, Serpico: The incredible, but true, story of the cop who couldn’t be bought! (New York: Bantam Books, 1974), 133.

- “What is a Whistleblower?” Government Accountability Project, https://www.whistleblower.org/what-whistleblower.

- David Burnham, “Graft Paid to Police Here Said to Run Into Millions,” New York Times, Apr 25, 1970, 1.

- David Burnham, “Policeman Tells Trial of Payoffs,” New York Times, Jun 19, 1970, 1.

- “Suspended Officer again found guilty of perjury charge,” New York Times, Nov 27, 1974, 27.

- David Burnham, “15 Police Trials Begin Tomorrow,” New York Times, May 2, 1971, 50.

- Doug Poppa, “Serpico sets the record straight, Part 7,” Baltimore Post Examiner, Jul 30, 2017, http://baltimorepostexaminer.com/serpicosets-record-straight/2017/07/30.

- Martin Arnold, “Man in the News,” New York Times, May 11, 1971, 27.

- “Excerpts From the Testimony by Serpico,” New York Times, Dec 15, 1971, 56.

- Whitman Knapp, The Knapp Commission Report on Police Corruption (New York: George Braziller, 1973), 4.

- Milton Mollen, Anatomy of Failure: A path for success (New York: The City of New York, 1994), 2.

- Molan, Anatomy of Failure, 1.

- “Frank Serpico Talks Ethics and Survival with EMBA Students,” Fordham News, https://news.fordham.edu/politics-and-society/frank-serpico-talks-ethics-and-survival-with-emba-students/.

My husband retired as a cop in Sarasota Florida in 2017. His Lt. back when he was a sgt had sex with a 14 yo girl who then got pregnant. He paid for an abortion and when the Lt.’s former roommate made comments about it my husband reporting it, it became the end of my husband’s career. He was removed as a detective then placed as a bailiff in the courthouse. He was harassed and suspended for a made-up charge. They let this Lt. be in charge of my husband and the Sheriff refused to investigate him or polygraph him. The icing was when this Lt was prompted to captain and retired full pay. My husband retired feeling demoralized and we have since moved to Pittsburgh. I would love it if Mr. Serpico has a few words to pull my husband up about sticking to his job as it meant something to be an honorable and just deputy sheriff. Thank you for your hard word and dedication to justice! Janice E Iorio

Re: Dominic Chris Iorio

Actually detective Chris Iorio was demoted after he failed to disclose to prosecutors that a young accuser had been previously sexually molested a few years prior. In early 2007, the then 8-year old girl spoke vaguely about being showed pornography and a boy exposing himself to her. The mother of the girl, Kelly Parisi, a Sarasota sheriffs department bailiff and acquaintance of Chris Iorio, pointed the finger at an innocent 21 year old man. That innocent man passed three (3) polygraph tests, 2 an administered by a former FBI polygrapher, and an 3rd polygraph administered by the sheriffs department itself. When his superiors discovered that Chris Iorio had withheld the previous molestation information from prosecutors, as well as that the accused had passed 3 polygraphs, he was rightfully removed from his position as a detective and given a post as a bailiff in the Sarasota county courthouse. Chris Iorio cared more about tallying arrests and securing convictions (innocent or not) than he did about pursuing justice.

Perhaps he made those accusations against the lieutenant as a way to salvage his reputation and be reinstated as a detective so he wouldn’t have to retire as a lowly bailiff.

I wonder if that was the first time he ever withheld evidence to bolster a case in the hopes of securing a conviction against an innocent person.

Can you imagine if it was your son Chris Iorio headset his sights on? Everyone thinks they are immune to something like that until it happens to them.

I’m here to tell you that you or someone you love can be 100% innocent and have all the witnesses and polygraphs in your favor, and still be put in legal jeopardy by a corrupt detective willing to throw you in prison knowing you are innocent.

Chris Iorio retired in disgrace because he is disgraceful.

Janice

Just came across your comment.

If still in contact

Hope you and Dominic are well

Frank Serpico

Serpicofrancesco@aol.com