The 2022 election saw a large number of women Independents become members of the House of Representatives. It’s now 100 years since Edith Cowan was elected as the first woman in any Parliament in Australia. What was it like to be elected as a woman to Parliament at that time and why is she so respected for what she achieved?

![]() This is Part I of a two-part series looking at the life and impact of Edith Cowan. Part II, Edith Cowan 100 years later – what’s changed for women in Parliament? examines how Edith Cowan’s experience as an MP compares to life for a woman in Parliament today.

This is Part I of a two-part series looking at the life and impact of Edith Cowan. Part II, Edith Cowan 100 years later – what’s changed for women in Parliament? examines how Edith Cowan’s experience as an MP compares to life for a woman in Parliament today.

DOWNLOAD Edith Cowan – Inspiration for Women Independent MPs. This printable pdf document combines Parts I and II and includes links to information sources.![]()

The main ambition of a woman’s life should be to become the wife of an honorable and honest man . . . It is man’s duty to be here [in this Chamber], and it is woman’s duty to attend to the family.”

——William Knox (Kooyong, Free Trade) House of Representatives, 23 April 1902.

Edith Cowan is best known for being the first woman to be elected to an Australian Parliament. While she did achieve a great deal in her one term of political office, we can also learn much from her trailblazing life of service to the community. After all, she was 59 when she entered parliament and was already highly respected for her earlier achievements. As an effective activist for change, she was a doer, not a complainer. As a Nationalist Party member, she was also fiercely independent.

Early life and childhood

Edith Dircksey Cowan (nee Brown) was born on 2 August 1861 at Glengarry Station near Geraldton, Western Australia, the second child of Kenneth Brown and Mary Eliza Wittenoom. Mary Eliza died while giving birth to their fifth child in 1868 and Edith was sent as a seven year-old to a boarding school run by two Cowan sisters in Perth. Their brother, James Cowan, would later become Edith’s husband.

Edith’s father, Kenneth had arrived from England with his parents, Thomas and Eliza Brown, in 1841 as a four-year old, accompanied by servants. The union would go on to produce six more children.

The first property Thomas purchased was Grass Dale in York, which he used for sheep and horse breeding. Although Thomas was intent on growing his wealth by purchasing tracks of land, he spent much of his time working for the Government as a land surveyor, magistrate and a brief stint a member of the Legislative Council. It was left to Kenneth and his brother Maitland to manage the properties at Grass Dale and Glengarry.

After the death of his wife, it seems Kenneth went into a downward spiral from being a successful explorer and pastoralist to losing money by gambling and drinking. Kenneth’s second marriage was to Mary Tindal in 1873 in Melbourne. Two more daughters were added to the four daughters and one son from his first marriage.

After time away living in Melbourne and New Zealand the couple returned to Geraldton in Western Australia late in 1875. On the afternoon of 3 January 1876 Kenneth, after a trivial argument with his wife, shot her twice in front of witnesses. She died at the scene.[1]

The subsequent criminal court cases made news around Australia. Here was a man of considerable means from a respected family with many connections in high places now on a murder charge.

It was difficult to find suitable jurors for the trial, one of the first in the colony as a ‘trial by jury’ in the Supreme Court. The population of Perth was only around 5,000 at the time, with roughly two-thirds being male.

The Age newspaper in Melbourne gave a long-winded, detailed report and commentary on the evidence presented at the trial:

[W]hen he [Brown] at length rouses himself to do the fearful deed, he deliberately fires at his victim as she flies shrieking from his presence, and when he perceives the shot is not fatal follows her to her place of retreat, and as she comes out from it and crouches before him in terror points the second barrel of his gun at her head and blows out her brains. All this occurs in open day, in the middle of a town, without any attempt to escape observation, and is proved beyond dispute.[2]

The news report goes on to debate whether a conviction of murder would still be the result even with the overwhelming evidence presented:

Defence, therefore, there was absolutely none, while there was an abundance of aggravating circumstances, one of them being the fact that the poor woman was near her confinement. But the reluctance of the colonists to convict a brother settler and bring disgrace on his connections was known to be so great that an attempt was made to offer such a show of evidence as might give an excuse to a friendly jury for bringing in a verdict of insanity.

The first trial before Chief Justice Burt was aborted after the jury could not reach a verdict. The same thing happened in the second trial. It was only after jurors in the third trial unanimously rejected the defence proposition that Brown was insane that a guilty verdict was reached on 25 May 1876. Brown was sentenced to death and was hanged two weeks later.

Edith faces a new life

Edith had suffered a painful childhood in losing her mother as a child. Now she had to endure the traumatic loss of her father and step-mother, plus the public humiliation of a father hanged for murder. Now aged 15, Edith left her boarding school to live with her paternal grandmother, Eliza Brown, in the Perth suburb of Guildford.

For the remainder of her school years she attended the Rectory School run by Church of England cleric Canon George Hallett Sweeting. Canon Sweeting had previously been Headmaster at the Bishop’s Collegiate School, founded by Bishop Hale in 1858, known today as Hale School. The late Peter Cowan, grandson of Edith Cowan, wrote in her biography, “Canon Sweeting left Edith Brown at least with a life-long conviction of the value of education, and an interest in books and reading”.[3]

By the time she had finished school it appears she was determined not to hide herself away from the public but to devote her life to be a champion for social justice for others:

On the family the emotional effect [of the father’s shame] was crippling, extending on into later generations. That it did not entirely inhibit Edith Cowan from a public life is, particularly given the conventions and attitudes of the time, remarkable. Indeed, it may very well have had the reverse effect, though at a cost recognized by those who knew her.[4]

Marriage and public life

In 1879 Edith married James Cowan, who had recently been appointed as Registrar and Master to the Supreme Court. She was eighteen; he was thirty and had been in numerous low-paying government jobs until this appointment. While James had minimal formal education he read extensively in law and became recognised for his legal knowledge.[5]

Between them, the Cowans had five children, four girls and one boy. No doubt Edith was busy with rearing their children before beginning her public life in 1890. James had by then been appointed as Perth Police Magistrate and Edith therefore became aware of the social problems of the day and the injustice meted out to women and children.

With her love for reading it is little wonder to find Edith become a member of the St. George’s Reading Circles which had formed by a school teacher, Miss A. J. Best, around 1877. Its purpose was to exchange and discuss reading material, and debate current affairs.[6]

A number of the members went on to form the first women’s club in Australia, the Karrakatta Club in 1894. According to the club’s history, the objective “was to bring into one body the women of the community for mutual improvement. Special engagement and advocacy were strong interests, and Club members championed local social justice issues affecting women.”[7]

Mrs A. Onslow, later Lady Onslow, was the first President. Edith Cowan was appointed as the first secretary and later became President. It was under leadership that the club became involved in women’s suffrage. Ultimately the right to vote was achieved in 1899.[8]

Edith suggested the motto for the club, Spectemur Agendo, let us be judged by our own actions. This was very much her own philosophy.

The next few decades are remarkable in what she achieved in her public life by either joining as an active member or founding numerous organisations. A newspaper report in 1921 summarised her community involvement:

She is a justice of the peace (being a member of the Children’s Court), president of the National Council of Women and the Soldiers’ Welcome Committee, secretary of the King Edward Maternity Hospital (for the existence of which institution she was largely responsible), a member of the Perth Public Hospital Board, on the committee of the Red Cross Society, and one of the founders of the Women’s Service Guild.[9]

Edith could have had a comfortable life as the wife of a public servant having a secure job. But according to her biographer, such a life would seem to her to be a waste, “cruel for the individual, and real for society.”[10]

During the Great War of 1914-18 Edith, although heavily engaged in social work, took on a range of war work:

The sheer number of committees on which she served or which she led would have made a full-time occupation. No one ever accused her of being an inactive member of anything she supported, and this work, with the vitally important social work that was undertaken in this period, did in fact totally consume her time through the years of the war until 1920.[11]

She received the Order of the British Empire (OBE) for work done during the war.

Meanwhile, her husband James had been forced to retire as a magistrate in 1914 to be replaced with men with legal training. In some ways this was fortunate as it allowed Edith to take on these additional roles.

From all these activities Edith gained extensive public recognition:

Few women in Australia, perhaps none in her time, had more publicity than Edith Cowan, yet she never ceased to assert that her causes were important, not herself . . . There had to be leaders, and she had the qualities of leadership, and through this, publicity came to her.[12]

Women for Parliament

There was a push dating back to the late eighteen-hundreds for the emancipation of women. This grew in the early decades of the 20th Century.

In Western Australia the law was changed in 1920 to allow women to be elected to Parliament. Most of the population welcomed the move but some men, especially politicians and even some women weren’t impressed:

The President of the Farmers and Settlers’ Association, however, still publicly deplores the intrusion of women into the legislative halls, and a correspondent in Saturday’s issue of the West Australian, while conceding the right of women to vote for “those men whom they think will best represent them,” considers that that should be the end so far as they are politically concerned. His view is that if a woman is unfortunate enough to be born “a woman, her mission is to marry, rear a family, and teach her girls to be domesticated.”[13]

It wasn’t expected that any women would be elected but there were four women candidates for the Western Australian Legislative Assembly election held on 12 March 1921. Edith, by now aged 59, was the endorsed candidate for the Nationalist Party, forerunner of the centre-right Liberal Party, in the West Perth electorate. She was up against another Nationalist candidate, Thomas Draper, the Attorney General who had introduced the legislation to allow women to become members of Parliament. She didn’t expect to win but she did with a 46 vote margin, becoming the first woman to sit in a Parliament in Australia. Voting was not compulsory at that time – until 1936 – and it was women voters, in particular, who enabled her win.

The result was a shock to the Nationalist Party:

They saw it in the simple terms of a disaster. They had lost an able and experienced party and cabinet member. They had gained a representative unknown politically, uncertain in terms of strict party allegiance, and a woman.[14]

The election of a woman to Parliament made news nationally and around the world. Although the report in the Melbourne Age was generally positive to the development it ended with a warning:

Were political office to become the ambition of the fair sex and were standing for Parliament to become the latest craze of fashion, there would be many dreary and neglected homes through out the country sacrificed on the altar of political ambition.[15]

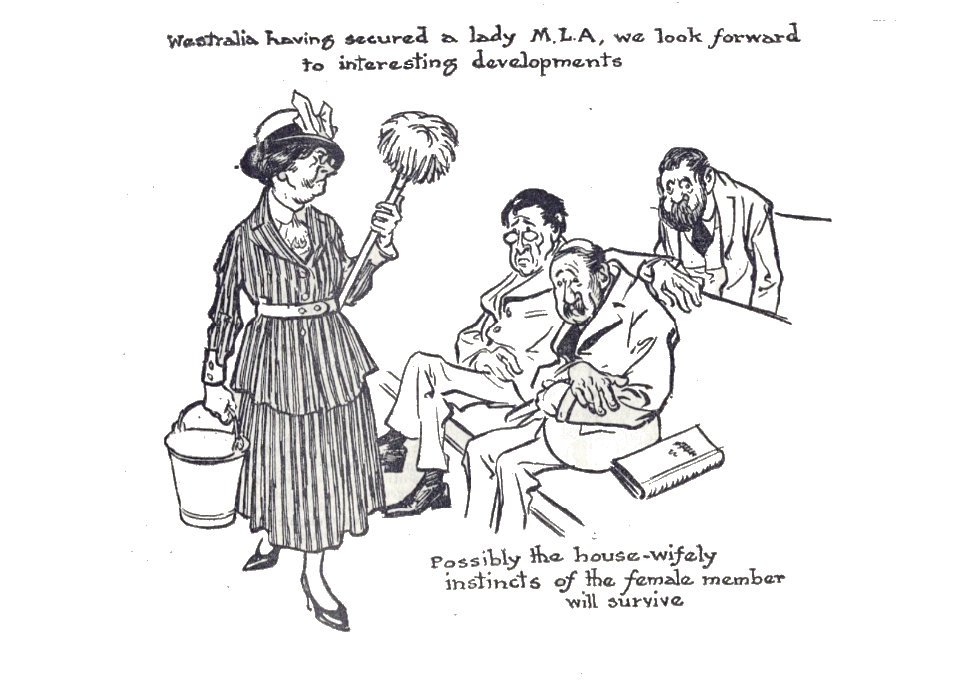

The Bulletin also lampooned Edith’s entry into the male domain of Parliament with a series of cartoons, with one showing the new member with a mop and bucket:

Edith had the right credentials to be a member of Parliament: well educated, intelligent and having leadership experience. A news correspondent added this description:

Of very forceful character, yet intensely sympathetic, a fine speaker, witty and logical, with a wide knowledge of social and economic questions, her advent into the House will be welcomed by people of many shades of thought.[17]

Edith’s entry into Parliament was not without its challenges. For one thing there were no female toilets in the building and consequently she had a four-minute walk to her home nearby – or perhaps it was a two-minute run.

It is customary in the Westminster system of Parliament that a member’s first speech be heard without interruption or interjection. In Edith’s case there were 17 interruptions or interjections during her speech. In thanking the government for passing the law to allow women to be elected to Parliament a member interjected with the comment, “They only wanted your vote.” But it didn’t put her off from her message that she was there to represent her constituents:

It is all the more necessary, therefore, that I should make it clear where I stand. I am a Nationalist, and I belong to no party in this House. I was sent here to uphold law and order and constitutional government, and it will be my desire to assist in carrying out these objects in a proper and satisfactory manner; while in the discharge of my duties here I shall be responsible only to my own constituents.[18]

Edith also believed more women elected to Parliament would benefit society by bringing in a women’s perspective:

If men and women can work for the State side by side and represent all the different sections of the community, and if the male members of the House would be satisfied to allow women to help them and would accept their suggestions when they are offered, I cannot doubt that we should do very much better work in the community than was ever done before.[19]

Edith was a very active contributor during her three-year term in Parliament. Having private members bills passed is rare but in Edith’s case there were two significant bills passed:

- The Administration Amendment Bill (1922) to give equal inheritance rights to mothers when a child died intestate.

- The Women’s Legal Status Bill 1923 to open the legal and other professions to women.

Other states had already passed similar legislation to allow women to take on roles in professions, such as law. Nevertheless, there was opposition from members who wanted to keep these professions in the male domain. One member interrupted her Second Reading speech of the Bill in September 1923, claiming, “You will be cutting all the solicitors and barristers out of their jobs.”

Another asked, “Surely you do not want generally to bring women down to the level of men?” to which she responded, “No, I want to raise men to the level of women.”[20]

Eventually the bill passed through both Houses without dissent. Her biographer summarised her achievements in Parliament:

To succeed in two private member’s bills was a considerable achievement in any parliament. She gained a reputation for precise speaking, a clear grasp of questions, and except on rear occasions . . . for reasonably brief and relevant contributions to debate.[21]

Some of her other political contributions[22] included:

- Fighting for proportional representation and compulsory voting.

- Giving strong representation to children’s rights, particularly in the court system and with health matters.

- Strongly advocating for free education with greater funding for education; and enhancement of educational standards for the nursing profession.

- Lobbying for regional development, tax incentives and infrastructure for schools, infant health centres, hospitals and roads.

- Strongly opposing gambling, alcoholism and lowering the drinking age below 21.

- Tabling a notice of motion to eliminate the ‘men only’ reservation rule to access all Parliamentary Galleries (now open to women and men).

Edith stood unsuccessfully for the elections held in 1924 and 1927. Her independent views had not always aligned with the policies of the Nationalist Party and she also had differences with some of the women’s movements. That didn’t stop her from being fully involved in women’s affairs but it was the end of her political career.

One cannot fail to notice that Edith is not seen smiling in any photos. Peter Cowan spoke of her serious nature and absence of emotion:

Hers was a difficult personality, its virtues – great courage, outspokenness, a remarkably clear and logical mind – were public rather than private virtues. She had great compassion, a keen sense of pity, which could spill over into public attitudes at times overstated. In private life these feelings were far more controlled – one might suspect repressed. She seemed often difficult to approach, was called at times hard, could appear in personal aspects abrupt, perhaps cold. In the hurt and confusion of childhood and early youth she learned a great distrust of emotion that could leave her vulnerable, it was too deep to be removed by her intelligence.[23]

Towards the end of the 1920s decade, she was observed to be less effective in her work with others, as one person reported:

Edith Cowan was tactless to a committee important to the National Council [of Women] dispute, that she adopted a high-handed attitude, antagonizing the members present, reflected an attitude easy to avoid in earlier years.[24]

She was admitted to hospital in April 1932 and died a few weeks later on 9 June with her funeral service taking place two days later. According to newspaper reports, a ‘large gathering’ attended, which is remarkable considering the short time for the news to travel.

Two years after her death, and after much controversy, the Edith Cowan Memorial Clock was unveiled in her honor at the entrance of Kings Park at Perth.

She has also been honoured with postage stamps and on an issue of the Australian $50 bank note.

In 1991 the Western Australian College of Advanced Education was renamed Edith Cowan University (ECU).

The Edith Cowan story shows that a woman parliamentarian with the right background can achieve significant change while they are in office.

Notes

[1] “Coroner Inquest into the death of Mary Ann Brown.” The Western Australian Times, 11 Jan 1876, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2975398?searchTerm=mary%20ann%20brown.

[2] “The Kenneth Brown Murder in Western Australia,” The Age, 26 Jun 1876, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/202160233?searchTerm=trial%20kenneth%20brown.

[3] Peter Cowan, A Unique Position: A Biography of Edith Dircksey Cowan 1861–1932 (Nedlands: UWA Press, 1978) 47.

[4] Cowan, A Unique Position, 46.

[5] Cowan, A Unique Position, 61.

[6] “Glimpses of the Past – Karrakatta Club Jubilee,” Western Mail, 30 Nov 1944, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/38558708.

[7] “History of the Club,” Karrakatta Club, https://www.karrakattaclub.com.au/history-of-the-club.

[8] “Edith Cowan,” TheFamousPeople, https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/edith-cowan-7227.php.

[9] “Mrs. Edith Dircksey Cowan, O.B.E., M.L.A.,” The Queenslander, 9 Apr 1921, 36, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/22610612.

[10] Cowan, A Unique Position, 53.

[11] Cowan, A Unique Position, 148.

[12] Cowan, A Unique Position, 71.

[13] “Women in Parliament,” The West Australian, 28 Mar 1921, 4, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/27959986.

[14] Cowan, A Unique Position, 165.

[15] “There are people in Australia who will have visions of an Imperialism,” The Age, 15 Mar 1921, 6, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/201698680.

[16] “The Women Should Have a Voice: Edith Cowan’s legacy of social justice in Western Australia,” Issuu, https://issuu.com/lswa/docs/brief-aug-2021/s/13039488.

[17] “Mrs. Edith Dircksey Cowan,” The Queenslander.

[18] Edith Cowan, “Inaugural Speech – Mrs Edith Dircksey Cowan, MLA,” Parliament of Western Australia, https://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/WebCMS/webcms.nsf/resources/file-edc100ar1921/$file/01.%20Address%20in%20Reply%201921.pdf.

[19] Cowan, “Inaugural Speech”.

[20] David Black and Harry Phillips, Making a Difference—A Frontier of Firsts: Women in the Western Australian Parliament 1921–2012, (Perth: Parliament of Western Australia) 2012, 85, https://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/parliament/library/MPHistoricalData.nsf/32e457f9ba7d7c5148257b5500242416/80e6430ba5f9a786482577e50028a588/$FILE/Making%20a%20Difference%20chapter%205.%20Edith%20Cowan.pdf.

[21] Cowan, A Unique Position, 220.

[22] “Edith Cowan Political Life,” Parliament of Western Australia, https://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/WebCMS/WebCMS.nsf/resources/file-heritage—cowans-political-life/$file/Edith%20Cowans%20Politial%20Life.pdf.

[23] Cowan, A Unique Position, 279.

[24] Cowan, A Unique Position, 280.