When the two young social entrepreneurs decided to start the Orange Sky mobile laundry service for homeless people in 2014 they had no idea where it would take them. Initially operating on a shoestring budget, Orange Sky now has an income of over $6 million. From just one location in Brisbane, there are now 250 sites offering weekly services to homeless people throughout all Australian states and mainland territories, plus the first Orange Sky mobile laundry van in Auckland, New Zealand.[1]

Let us not develop an education that creates in the mind of the student a hope of becoming rich and having the power to dominate [but one that forms] the lofty ideal of loving, of preparing oneself to serve and to give oneself to others.

– Archbishop Oscar Romero

Note: This blog post is an update to the blog initially posted on December 20, 2016.

How Orange Sky started

It was June 2014 and 20-year-old Lucas Patchett had just returned to Brisbane from a working holiday in Canada. He was about continue his Mechanical Engineering course at the University of Queensland when he caught up with his ex-school mate, Nicholas Marchesi. Together they came up with the idea of starting a mobile laundry service for homeless people. Pachett deferred his university study and Marchesi gave up his job as a TV cameraman. Within weeks they had registered the name Orange Sky Laundry and were working franticly to fit out Marchesi’s old van as a mobile laundry.

When the two of them eventually took their bright orange mobile laundry van on its first outing on October 10, 2014, they weren’t sure what sort of reception they would get. They had spent weeks fitting out the van with two donated washing machines, two dryers, water tanks and power systems. Some people said it was a crazy idea.

They drove the van they called “Sudsy” to a park where food was being given out to homeless people. At first there was confusion as no one had come across such a thing as a mobile laundry for free. What was the catch?

One person, Jordan, had two T-shirts in his backpack and was willing to give it a go. Lucas chatted with him while the washing machine did its job and was amazed to find Jordan had completed, some eight years earlier, the same engineering course Lucas was currently undertaking. Somehow things had gone wrong and Jordan had lost his job and without family support had ended up on the streets.

That night Marchesi and Patchett proved their belief there was a need for a free laundry service but also recognised the importance of listening to people’s stories in a non-judgemental way as they waited for the clothes to be washed and dried. From that point on they always carried six orange chairs with them for their “conversations with friends”.

Facts About Homelessness

In Australia it’s often stated there are over 110,000 people homeless each night and the number is growing. This figure is based on the latest data available, the 2016 Census conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).[2]

According to the ABS, around 60 percent of these homeless persons live in severely crowded dwellings or stay in supported accommodation for the homeless. Another 35 percent are homeless persons staying temporarily in other households – they are often described as “couch surfers” – or else are staying in boarding houses. The majority of people who become homeless do so for short periods of time but a few are long-term homeless. Research also tells us that one in eight Australians have been homeless at some point in their lives. Around 40 percent of homeless persons are between 12 and 24 years of age with the possibility of some becoming long-term (chronic) homeless persons. It’s estimated that some 8,000 persons sleep rough each night throughout Australia.

People can become homeless for a variety reasons. Lack of affordable housing, coupled with poverty and unemployment are key structural factors. Personal circumstances such as poor physical or mental health, substance abuse, gambling, family breakdown, domestic violence and physical and sexual abuse are reasons homelessness may occur.

No one wants to be homeless but it can happen to anyone. John, 48, had a job earning him $150,000 a year as a pest exterminator but things suddenly went wrong when he was severely injured when he went to save a young child from injury. He then lost his job and shortly after split up with his partner. He was last reported to be living on the streets in downtown Melbourne.[3]

Living rough is uncomfortable, unhealthy and dangerous. Homeless persons on the street are avoided by most people who won’t even look them in the eye, as if they don’t exist. Others attack them for sport, for the fun of it. Fifty percent of homeless people admit to being attacked physically or sexually. Some have been murdered by being set on fire or knifed. Many instances of attacks go unreported.

Governments are taking steps to alleviate the lack of suitable housing for the chronically homeless but there seems to be no end to the numbers of short-term homeless who, in many cases, just need a little help to get back on their feet.

Friends with a common mission

Nic and Lucas became friends while attending the same high school, St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace in Brisbane. Terrace is described as one of Queensland’s most prestigious private schools. Founded in 1875 by the Christian Brothers it has a rich history. Among Terrace’s alumni are 15 ex-students who have played rugby for the Wallabies, Australia’s national rugby union team. There are also 18 Rhodes Scholars, and, since 2013, a judge on the High Court of Australia.

In 2019 Terrace was ranked among the top 10 private schools in Queensland for academic results.[4]

But Terrace offers much more than academic results and sport. It is one of the 50 schools operating in Australia under the Edmund Rice Education Australia (EREA) umbrella and is grounded in the Edmund Rice tradition of developing “a young man of faith and learning who will make a difference to community through his knowledge, humility and wisdom.”[5]

Edmund Rice was a truly remarkable man, a person we would describe today as a social entrepreneur, that is, someone who establishes an enterprise with the aim of solving social problems or effecting social change. See Edmund Rice – Social Entrepreneur.

Many of the students at St Joseph’s Terrace come from comfortable backgrounds and are destined for a life ahead of them in high-paying careers. Other students may come from families who are not so well off but make sacrifices to give their children the best education they can.

One of the many Terrace ex-students who have absorbed the social justice message of Edmund Rice is Anthony Ryan, currently the CEO of Youngcare, a national not-for-profit organisation helping young Australians with high-care needs.

After leaving Terrace in 1987 he started studying Economics at the University of Queensland with the intention of becoming a stockbroker.

It was while he was visiting his brother who was working to assist homeless in Washington DC that he became exposed to the plight of the homeless. On his return to Australia he decided to become a teacher. “I saw another side of life that I thought I could have an influence on,” he said in a 2013 interview.[6]

In 1998 he was back at Terrace but now as a teacher. He wanted to create opportunities for students not to just learn in a classroom. “I wanted to make it experiential and I wanted them to challenge their stereotypes,” explaining his approach.[7]

Service Learning and Social Justice

Together with Christian Brother Damien Price, Ryan established Eddie’s Street Van in 1999. The purpose was twofold. It would offer hot food and drinks to some of Brisbane’s homeless and would teach students about what it was like to have nowhere to live. Damien Price describes it as a gap to be bridged. One the one hand there are students from comfortable backgrounds who in most cases will not experience homelessness and will have the mindset that “the situation of homelessness is one of their own making and they should straighten themselves out and get a job.”

In a social context, the “other side” of the gap are often reduced to stereotypes, such as: Asians, Muslims, asylum queue-jumpers, dole-bludgers, druggies and gays. Even politicians and radio “shock jocks” use labels such as street gangs, leaners (those accessing government welfare) and illegals (asylum seekers who arrive by boat).

The pedagogy used for students to cross the bridge is called service learning. Susan Benigni Cipolle, author of Service-Learning and Social Justice, offers the following definition:

Service-learning is a learning strategy in which students have leadership roles in thoughtfully organized service experiences that meet real needs in the community. The service is integrated into the students’ academic studies with structured time to research, reflect, discuss, and connect their experiences to their learning and their worldview.[8]

When it is managed well Cipolle says service learning results in “increased self-awareness and the ability to make a difference, increased awareness of others and an increased awareness of social issues.”[9]

Price warns of the detrimental effects if such a program is not managed properly. “There is a danger that [the student’s] prejudice could be reinforced, false conclusions come to and stereotypes enhanced as a result of the service experience,” he says.[10] To the homeless person, it comes across as being patronising, demeaning and disrespectful.

Ryan says the idea of the program wasn’t just about feeding the homeless. “It was going beyond charity and was about actually sitting down with the people, making the students go out and actually mingling with homeless people, hearing their stories.”[11] These people are no longer “the homeless” to students but are identities with names and faces.

By the time Marchesi and Patchett attended Terrace, Anthony Ryan and Damien Price had moved on but the service learning program continued. Both were volunteers for Eddie’s Brekky Van when they were in Year 11 and Year 12, 2010-11. In Year 12 both were house captains and that’s when their friendship grew.

Eddie’s Van still operates weekday mornings with the Terrace student volunteers up early cooking breakfast and serving the homeless people in central Brisbane. Former students of Terrace also man Eddie’s Van at night serving tea, coffee and soup.

Orange Sky’s Growth

In the five years since that inauspicious, mostly self-funded start by Marchesi and Patchett, their little enterprise has grown dramatically to have a major social impact in the communities it serves.

It’s not just the clothes being washed and availability of showers that’s important. They believe it’s the conversations with their homeless friends that make Orange Sky such a powerful force for reconnecting with people. Patchett cites the case of the man who had his clothes washed hadn’t spoken to a single person in the previous three days. As a result, the Orange Sky mission has evolved from providing clean clothes to positively connecting communities.

Orange Sky started purely as a not for profit (NFP) enterprise. Tom Ralser, a non profit specialist, has identified three paradigm shifts in relation to not for profit organisations:

- A change from a gift-giving, donation mentality, where no return is expected, to an investment mentality where a return on that investment is expected.

- A focus on results or outcomes rather than on the outputs or services provided.

- A move beyond emotional appeals in fundraising to a business-like, return on investment approach.[12]

After several years of operating Orange Sky, Marchesi and Pachett would understand exactly what Ralser is saying, even if they’ve never heard of Tom Ralser. Orange Sky is still a registered charity but is now in the process of combining this with a ‘profit for purpose’ or a ‘social enterprise’ business model where social enterprises can be defined as “businesses that trade to intentionally tackle social problems, improve communities, provide people with access to employment and training, or help the environment.”[13]

Whereas a NFP relies on funding from external sources, such as government grants and fund raising to operate, a social enterprise performs a social good and generates a profit from trade. In this way a social enterprise is less reliant on donations and grants to be sustainable and to grow.

But what sort of trade could Orange Sky undertake? They certainly have no intention of charging homeless people for clothes being washed or for showers. One answer is to offer cleaning services to other businesses for a fee. Another major opportunity is to offer the technology Orange Sky have been developing in-house to other volunteer organisations to run their operations.

The use of technology has been important in Orange Sky’s operations and is seen to be more advanced than many other non-profit organisations. As Marchesi explains, “We’ve used lots of tech right from the start because we quickly realised the more we used it the more people we helped.” He adds:

We use technology across every part of our organisation. It has enabled us to work more efficiently in every area, from our administration, to telling people about what we do, to ensuring the safety of our volunteers, to getting more donors on board. It’s everywhere.[14]

In October 2018, Orange Sky was given the People’s Choice Award of $1 million in the Google Impact Challenge Australia. The grant has enabled development of Orange Sky’s own systems into the Campfile software application to be made available “to empower other volunteer driven organisations with the tools to amplify their social impact, and connect with their volunteers.”[15]

The availability of Campfire was announced on November 11, 2019.[16]

Marchesi says all surpluses (profits) generated will be reinvested in the business.

Measuring the Social Impact of Orange Sky

From the very beginning Marchesi and Patchett were aware of the difference between outputs – clothes washed – and outcomes – the experience of a homeless person feeling connected again.

The advisory firm Deloitte defines an output as a “good or service produced or delivered.” Orange Sky outputs include washes, showers, conversation hours, employment hours and referrals to other service providers. On the other hand, an outcome is defined in the social context as “a change experienced by a person, family or community.” [17]

Deloitte has assisted Orange Sky in measuring the value of its outcomes and for the 2018-2019 financial year assessed Orange Sky’s impact in the community as being $9.5 million. This means that every dollar invested returns $1.70 in social impact.

By showing the social impact of Orange Sky’s operations, governments, benefactors and investors can see the multiplier effect of any contributions they might make.

This result wouldn’t have been achieved without the involvement of more than 1,800 volunteers in Australia, together with the Orange Sky partners, sponsors and donors and more than 40 full-time Orange Sky staff.

On 25 January 2016, Australia Day, Marchesi and Lucas were named the 2016 Young Australians of the Year. This award has given publicity for Orange Sky and the opportunity for the two or them to tour the country in 2016 to tell their story and speak about their mostly forgotten friends, the homeless.

Further recognition took place four years later when both were announced as recipients of Australia Day 2020 honours – the Medal of the Order of Australia (OAM).

Social Entrepreneurship Theory of Change

What seems to be a spur of the moment decision by Marchesi and Patchett to start a free mobile laundry actually had years of nurturing as the foundation before entering into the path of social entrepreneurship.

Bornstein and Davis suggest that a social entrepreneur requires a theory of change to show the path for spreading their idea, achieving the desired impact and influencing others.[18]

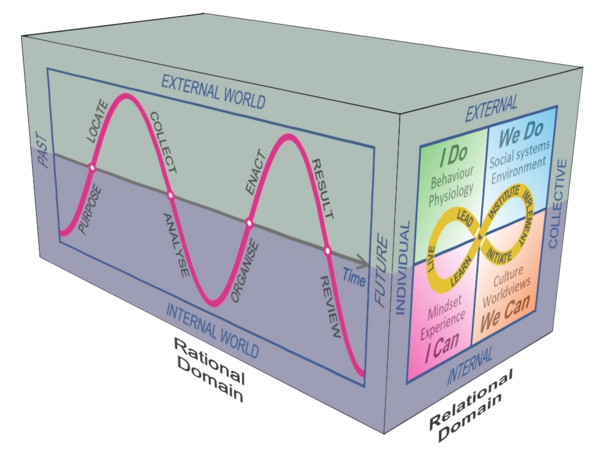

One theory of change model is the Can-Do Wisdom Framework. The Relational Domain of the model is shown in the diagram below is made up of four quadrants: I Can individual/internal, I Do individual/external, We Can collective/internal and We Do collective/external.

The gap that Damien Price talks about is between the I Can quadrant and the We Do quadrant, specifically the initial mindset of students based on commonly-used labels and the social system that has allowed homeless people to exist in a wealthy country like Australia.

Social Entrepreneurs Learn

Both Nic’s and Lucas’ mindsets about social justice and homelessness were developed and changed from their service learning experiences at school. Their immersion in the program gave them a level of empathy they wouldn’t have had before. They had also been given life-long guidance by their parents who have been highly supportive of their efforts. For example, Nic’s mother, has worked in the area of homelessness and believes everyone has the right to safe, secure and affordable housing.

Nic and Lucas know that others in their social group are looking for something meaningful in their lives and it has been their vision from the beginning to tap into that resource for volunteers.

Social Entrepreneurs Live

Both Nic and Lucas are people of action and have the courage and fortitude to persevere when others tell them their idea is crazy. Nic is highly creative and doesn’t take no for an answer. He was running his own business while still a high school student.

Lucas says they have fun working together and complement each other nicely:

Nic’s strengths lie more with research and development; the technical side of things — he is the handyman. He’s been instrumental in building the vans and understanding how they work. I’m better with modelling, data capture and quantifying our impact.[19]

Social Entrepreneurs Lead

Nic and Lucas took direct action themselves to address a need they could see. Other than the initial donation of two washing machines, they poured their own resources of money and time into the project.

Being savvy with social media and having great presentation skills has meant they have gained a world-wide following and have received extensive press coverage that any business owner would die for.

Receiving the Young Australian of the Year award for 2016 meant they had the opportunity to address groups around the country into what they were doing.

Social Entrepreneurs Initiate

Through the use of effective communication channels Nic and Lucas have had great success at recruiting volunteers, initially from their circle of friends, but now Australia-wide. There are now 1,800 participating in regular shifts at the 29 vans now operating across all states of Australia.

Since it costs $100,000 to put a van on the road, this would not have been possible without sponsorship and donations.

Strategic planning for Orange Sky is performed in the We Can quadrant and is focused on how to achieve a social impact of $11.5 million in the 2019-2020 financial year. This is where the Rational Domain of the the Can-Do Wisdom Framework comes into play.

Showing Can-Do Wisdom Framework Rational Domain

Showing Can-Do Wisdom Framework Rational DomainSocial Entrepreneurs Implement

Training volunteers is an important aspect of providing a consistent service along with having a distinctive brand. The name Orange Sky comes from a song by British musician Alexi Murdoch about helping those in need.

These vans are much more advanced than the initial van they put together themselves.

The Orange Sky organisational structure has also developed with an experienced board of directors and more than 40 employees.

Social Entrepreneurs Institute

What they’ve done for homeless people in washing their clothes for free has been well received. But it’s the non-judgemental interactions with their “friends” that has made a difference to lives. In the five years since starting out Orange Sky “friends” have benefited from 1.3 million kilograms of clothing being washed, from 13,000 showers and over 200,000 hours of positive, genuine and non-judgmental conversation has taken place. In some cases those who have recovered from their stint at being homeless have come back as volunteers.

But it doesn’t stop there. By being present in the external environment means Orange Sky learns from mistakes and becomes aware of new challenges and opportunities. In this way one continues through the Learn, Live, Lead, Initiate, Implement, Institute pathway. This is exactly what Orange Sky have done in modifying their mission and delivering the Campfire system.

The Importance of Social Entrepreneurs

Nicholas Marchesi and Lucas Patchett, together with the Orange Sky team, demonstrate social entrepreneurship in action.

Even if a government was committed to deliver such a project, imagine the time taken, the cost involved and the likelihood of a poor result. There are plenty of examples of failures government initiatives, such as the “Energy Efficient Homes Package” where two people died, and the systemic failure of the Vocational Education and Training (VET) funding system resulting in billions of dollars being wasted for little return.

Governments typically approach issues from the outside. For example, the Indigenous programs designed in Canberra consistently do not achieve their goals in improvements in violence levels, health, school attendance and household budgeting and purchasing.

Social entrepreneurship understand problems from the inside. Their measure of success in the achievement of the desired outcome for the recipients of a program.

It’s also becoming increasing apparent that governments are often failing to deliver needed services and support to sections of the community. They are also often failing to safeguard the environment, protect human rights, collect appropriate royalties and taxes from multinational corporations, regulate financial institutions, and ensure workers conditions and pay are fair.

The 9/11 events have shown us what a small number of terrorists can do to a nation. But Bornstein and Davis suggest it also means that a small number of citizens acting as social entrepreneurs can also achieve much good for a community, for a nation and for the world.[20]

Kickul and Lyons identify several unique qualifications that social entrepreneurs possess. These include passion, nimbleness, transformation enabling, mission focus, and social innovation.[21]

Some governments are recognising the importance of social entrepreneurs because public funds are under increasing pressure from reduced economic growth. In 2016, Australia was ranked 26 for the best country for social entrepreneurs in a survey of 42 countries. The latest survey by Thomson Reuters Foundation conducted in 2019 ranks Australia as number two in the world—a dramatic improvement. Forbes reports on the reason for the change:

Since 2016, the nation has improved significantly to create a productive environment for social entrepreneurs. It’s also done a great job garnering support from both the government and the general public. If you’re not afraid of spiders, Australia is a great place to start a technology-based social enterprise, especially for those seeking investments.[22]

Social entrepreneurship is vitally important for us in the twenty-first century as a means for social improvement and making the world a better place. Social entrepreneurs need to possess the skills of empathy, teamwork, leadership and driving change. We all need to recognise this and play a part in either pursuing or encouraging the development of these skills as St Joseph’s Terrace does for its students.

Notes

- Orange Sky Australia Ltd, 2018/2019 Annual Report, https://orangesky.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/annual-report-2019-v4-compressed.pdf.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population and Housing: Estimating homelessness, 2016, Cat. No. 2049.0, Canberra, 2018, https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/2049.0.

- Aisha Dow, “Shocking’: Record numbers of homeless people sleeping on Melbourne’s streets,” The Age June 9, 2016.

- “UPDATED: Brisbane Secondary School Ranking | OP/ATAR results in Grade 12,” Families Magazine, February 24, 2019, https://www.familiesmagazine.com.au/secondary-school-ranking-year-12-results/.

- “St Joseph’s College, Gregory Terrace,” Edmund Rice Education Australia, http://www.erea.edu.au/our-schools/erea-member-schools/st-joseph-s-college-gregory-terrace.

- CatholicEdWeek, Catholic Education Week 2013 – Making a Difference…… Inspired by Jesus (online video, July 7, 2013). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NPfKEsq-uqc.

- CatholicEdWeek, Catholic Education Week 2013.

- Susan Benigni Cipolle, Service-Learning and Social Justice (Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010), 4.

- Cipolle, Service-Learning, 19.

- Emilie Ng, “Reaching out to the margins makes better students,” The Catholic Leader, April 20, 2016, https://catholicleader.com.au/education/this-queensland-based-community-organisation-has-sent-its-first-gestures-of-love-including-food-to-refugees-in-nauru-2.

- Mike Bruce, “Damien Price a brother in alms,” The Sunday Mail (Qld), May 15, 2011, https://www.couriermail.com.au/ipad/damien-price-a-brother-in-alms/news-story/59eb7e0ff3a8589a0bd7698ef9202433.

- Ralser, Tom, ROI for Nonprofits: The New Key to Sustainability (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2007), 21.

- “We make winning work easier for social enterprises,” Social Traders, https://www.socialtraders.com.au/social-enterprise/#overview.

- “Why the Sky’s the limit for tech-savvy Aussie not-for-profits,” Connecting Up, https://www.connectingup.org/about/case-study/why-sky-s-limit-tech-savvy-aussie-not-profit.

- “It’s been 12 months since we won $1 million…here’s what we’ve been up to,” Orange Sky Australia, https://orangesky.org.au/one-year-on-from-google-win/.

- “A better way to do volunteering,” Campfire, https://campfireapp.org/.

- “A practical guide to understanding social costs: Developing the evidence base for informed social impact investment”, Deloitte Access Economics, Feb 2016, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/au/Documents/Economics/deloitte-au-economics-understanding-social-costs-practical-guide-140216.pdf.

- David Bornstein and Susan Davis, Social entrepreneurship: What everyone needs to know (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 50.

- Amy Braddon, “Two Up: The Sky’s the Limit,” Company Director Magazine, 26 Mar, 2018, https://aicd.companydirectors.com.au/membership/company-director-magazine/2018-back-editions/april/two-up-skys-the-limit.

- Bornstein and Davis, Social entrepreneurship, xvii.

- Jill Kickul and Thomas S. Lyons, Understanding Social Entrepreneurship: The Relentless Pursuit of Mission in an Ever Changing World (New York: Routledge, 2012), 5.

- “The Best Country To Be A Social Entrepreneur In 2019,” Forbes, Oct 26, 2019, https://www.forbes.com/sites/khaitran/2019/10/26/the-best-country-to-be-a-social-entrepreneur-in-2019/#3ca39b96dd37.

Great piece of work Adrian! You’ve made some very relatable connections between social entrepreneurship and your Can-Do Wisdom model. Further proof of the universal applicability of the Can-Do Wisdom concept. Working in the Aged Care sector myself for a company that specialises in aged care for the homeless and those at risk of becoming homeless, I have always considered it a vital part of my role to listen to our clients in an unjudgmental way while performing my “paid” duties as a maintenance worker. This positive interaction can be applied to any worker whether paid or volunteering to help them reconnect with society. I cannot make representations on my employer’s behalf but I will be forwarding this article to my leadership group to hopefully start some discussion around how this groundbreaking technology pioneered by Orange Sky could help us with our mission to serve those in need in our community.

Joe Capraro

Hi Joe, I’m glad you can make use of the article. Hope something useful comes out of your discussions. As you can probably tell I’m really impressed with what these guys and the team of employees and volunteers are doing. We haven’t heard the last of them, that’s for sure.

Cheers

Adrian