Judy Courtin wasn’t the first to call for a Royal Commission to investigate sexual assault and the Catholic Church; victims of child sexual abuse, lawyers and advocates had been calling for one for years.

It was only in 2006, after her mid-life career change from being a chiropractor to becoming a human rights lawyer, that she learned a close family member had been abused at school by a Christian Brother. This inspired her to learn more about the difficulties faced by victims of child sexual abuse by Catholic religious. Her unique insights would bring a fresh look to an age-old problem. And she made sure her call for a Royal Commission was heard.

This is the story of how she did it.

Never see a need without doing something about it.

– Mary MacKillop

Who is Judy Courtin?

Judith Edwina Courtin grew up in Melbourne, the fifth of seven children of Edward (Ted) and Agnes (Billie) Courtin. Her father was born in London and had come to Australia as a 12-year-old boy to live with his uncle, Bert Courtin, after his parents divorced. Ted later became an apprentice to Bert in his film processing business. Judy’s mother, Agnes Bliss, was a classically-educated musician and singer who first met Ted when he studied music with her when he was in his late 20s. Ted enlisted in the Australian Army in 1942, training as a commando. They married in 1943 before Ted was sent overseas on war service, returning to civilian life again in 1946. Ted was then a journalist before he established a printing business known as Commando Printing Services, which is a business still operating today.

Judy describes her home life in the 1950s and ‘60s as follows:

Mum was Catholic; my father was not. We were brought up with very broad social-justice values. Mum always stuck up for the underdog and we were all taught to stand up and not take shit from people. Also, we were taught to not let someone else take shit if they could not look after themselves. Through my childhood we often had extra people living with us as they didn’t have anywhere to live or were in some sort of strife – at one stage we had a young woman and her baby with us – her husband was in prison. So, looking out for others was sort of infused into us over the years.[1]

According to Judy’s sister, Robina, even though their parents were far from wealthy, they wanted their children to be educated at leading Catholic private schools.[2] The three older girls, starting with Jan, attended Sacré Cœur Convent until the money ran out. Judy ended up boarding in several schools and left before completing Year 12.

She spent the next few years drifting before taking up her studies again at age 26. Judy completed a Bachelor of Health Science/Bachelor of Applied Science (Chiropractic) degree at RMIT University and in 1981 obtained registration as a chiropractor.[3]

Judy Courtin’s mid-life career change

After a career of 25 years as a health practitioner, Courtin decided she wanted to work in the area of social justice and human rights. She enrolled in the Law faculty at Latrobe University and graduated with Honours in 2004. Her honours thesis identified a disturbing situation in Victoria whereby “more than half of child sexual assault convictions are appealed and about half of the appeals are allowed.”[4]

According to data sourced from Victoria Police, 1785 people reported penetrative offences, other than rape, during the period 1997–98 and 1998–99. Such offences include incest and sexual penetration of a child under 16 years. However only 14.5 percent, or less than 1 in 7 of these reports proceeded to prosecution and of these cases 116 convictions resulted.[5]

Courtin pointed out in her 2006 paper that when appeals are taken into account, the result is a 6.5 percent conviction rate. She described this is as “a glaring disincentive for a complainant seeking justice through our criminal justice system to report offences to police.”[6]

The focus of her thesis and research was on the legal system, and not on the victims of child sexual abuse. This changed dramatically in 2006 when she was told by a close family member that he had been abused as an 11 year-old schoolboy by a Christian Brother. She was shocked by what had happened to him and the difficulties he was experiencing in having his grievance heard by the Church’s internal complaints processes. She decided to investigate and learn more about these two complaints processes, the Melbourne Response and Towards Healing. She also spoke to legal advocates and other victims and their families. It became clear to her there were great difficulties for victims to obtain justice, civil or criminal, and she saw the uncaring response by the Church was actually another form of abuse suffered by victims and their families.

In 2010 she embarked on a doctoral project to thoroughly research the matter of sexual abuse and the Catholic Church in Australia. By mid-2011 her research had made it clear to her that “an independent and State-run inquiry of these issues was urgently needed.”[7]

This conclusion that a Royal Commission was needed had also been reached by others but their calls went unheeded. For example, the Broken Rites organisation had been set up in 1992 to help victims of church-related abuse. Over the years their volunteers had collected a mass of information from victims and had set up a website detailing the crimes committed by priests and the behaviour of church leaders who hid the problem. They had first called for a Royal Commission in 1999.[8]

Doing something about it

Starting in mid-2011 Courtin she did something very smart by making her key findings available to the public. It is a case study in how an academic research project can increase public knowledge to justify change.

Referring to the Can-Do Wisdom Framework below, so far Courtin had learned in her I Can quadrant about the social systems and environment used by the Catholic Church and the legal system in the We Do quadrant that adversely affected victims of child sexual abuse. All this was stemming from the culture in the largely hidden world of the We Can quadrant, which in the case of the Catholic Church could be described as, ‘we can do what we like.’ Any change initiative instigated by Courtin now centred on what she could to do in the I Do quadrant to influence a change of culture in the We Can quadrant, in turn resulting in change to the social systems and environment in the We Do quadrant.

Can-Do Wisdom Framework: Relationship Domain

Can-Do Wisdom Framework: Relationship DomainThe question then became, how could she transfer her knowledge to a wider audience to achieve the immediate goal of an independent judicial inquiry?

Writing an academic dissertation is very different from writing op-ed opinion pieces and letters to the editor in a world of fast-paced media. Dr Carrie Baker is an academic researcher, journalism award winner and author of the book, The Women’s Movement Against Sexual Harassment. She says writing 50-word sentences is accepted in academic work but adds, “I want my academic work to be relevant to the broader world. . . . let’s bring this to a level where it can be popularly consumed.” [9]

Social scientist and author, Lee Badgett, has learned first-hand the secrets of engaging with a wider audience. In her book, The Public Professor: How to Use Your Research to Change the World, she shares her framework and techniques for how academics (and others) can get policymakers, the media, and community members to pay attention:

1 See the big picture: the terms of the debate and the rules of the game.

That means understanding both sides of the debate even though you will only be supporting one side. It also means understanding how change happens through courts and legislative change and see how influential actors operate in the public debate.

2 Build a network of relationships that extends into the work and institutions you hope to influence.

In this phase you need to identify all the players in the sphere you’re working in. This would include like-minded activists, community organisations, journalists, policy makers and their staff. As Badgett explains, “They will work with you because you have something that they need, so ask them how you can be useful.”[10] Having accepted your message, they can have a multiplier effect by making your message heard in their network. Badgett says the key to influencing policy is to persuade others to include you in their networks. The bigger your network, the greater your influence.

3. You need to know how to communicate ideas to people who aren’t in your field.

Academics are comfortable with the jargon used in their field because it’s an efficient way to communicate between colleagues. You need to learn a range of communication approaches that suit a wider range of audience, making use of presentations, blogs, tweets, newspapers, television and radio shows, and briefing papers.[11]

Courtin’s media campaign starts

With the goal of achieving a Royal Commission in mind and encouraged by her colleagues at Monash University, Courtin began her public communications strategy modestly in 2011 with letters to the editor published in the Melbourne Age newspaper in October and December. These letters were in response to news articles published the previous day. The key to having a letter to the editor published is providing a piece which is timely, relevant and well written. She sent her letters off the same day the original articles appeared.

The news item that stood out for her on 18 December 2011 had the headline ‘Judges’ miscarriages of justice’ with the sub-head, ‘Judges’ mistakes in instructing juries in child sex cases have caused almost two-thirds of retrials ordered in Victoria this year.’ This was the topic she had researched seven years earlier and with her letter she was able to share her knowledge of the subject, adding strength to the original article.

In 2011 Courtin had two letters published in The Age, one in May followed by another in June. Then something interesting happened. Her expertise was being recognised and she began to be quoted in news items in The Age and the Sydney Morning Herald. Then in September and October she was interviewed by ABC radio in national news programs. Her one op-ed for 2011 was published in The Age on 14 October under the headline, ‘Victims of clergy need justice now.’ Overall there were 14 Media appearances in 2011 captured in the ProQuest Australia & New Zealand Newsstream database.

The breakthrough year of 2012

A big news story broke on 13 April 2012 when The Age investigation team told of leaked Victoria Police report the newspaper had obtained. The report was written by Ballarat detective Kevin Carson who had been investigating the behaviour of priests and brothers in the Ballarat area of Victoria for decades. The introduction to the news story read:

Confidential police reports have detailed the suicides of at least 40 people sexually abused by Catholic clergy in Victoria, and have urged a new inquiry into these and many other deaths suspected to be linked to abuse in the church.[12]

Courtin’s own research had uncovered clusters of suicides by victims of child sexual abuse and she was interviewed about this by the ABC Lateline TV program the same evening.[13]

On the following day her first op-ed piece was published, giving reasons why a Royal Commission must be held to expose the truth.[14]

Four days later the Victorian Government announced the inquiry they had been considering for some time but not acted on. The ‘Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and other Non-Government Organisations’ would not have the powers of a Royal Commission meaning, as Courtin pointed out in interviews, was not going to expose the full truth.[15]

Several months later the NSW government announced the appointment of a ‘Special Commission of Inquiry into matters relating to the investigation of certain child sexual abuse allegations in the Catholic Diocese of Maitland-Newcastle.’ This also had limited scope when a wider inquiry was clearly justified.

The major media event for Courtin during 2012 was to appear as a guest on Michael Short’s multimedia production of The Zone for Fairfax Media on 25 June.[16]

Her next op-ed came in September when she accused Church leaders of not being sincere when they say they put “abuse victims first”.[17]

The third op-ed came in December after the Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, announced a Royal Commission would be held. Courtin reminded readers that it was the victims, their families, their advocates and the media that forced the politicians to finally act. In doing so she praised the politicians for ignoring Cardinal Pell’s protests that the Catholic Church “had been unfairly vilified,” and his claim that “Anti-Catholic prejudice is one of the few remaining prejudices.”[18] The Royal Commission would ultimately find, “Based on the information before us, the greatest number of alleged perpetrators and abused children were in Catholic institutions.”[19]

The ProQuest count for news media exposure during 2012 had increased dramatically for Courtin from September onwards. Her op-ed work also included a series of pieces for the academic-related web site, The Conversation.[20]

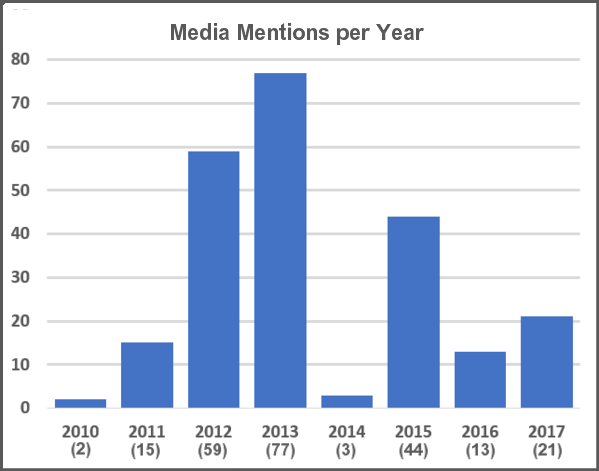

The exposure would increase even further during 2013 as shown in the bar chart below.:

Judy Courtin Media Mentions in ProQuest Database[21]

Judy Courtin Media Mentions in ProQuest Database[21]These media mentions were either in newspapers, mainly Fairfax publications, wire services or radio and television interviews, mostly on the ABC broadcasting network. The multiplier effect of her network of journalists was clearly working.

Victorian Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse

On 28 February 2013 Courtin presented to the Victorian inquiry. She gave graphic details of the abuse victims had received and described the effects of that abuse on their health, their families, their education and the unacceptable high number of suicides.[22]

Research by Margaret Cutajar et al. has shown the clear link between child sexual abuse and suicide and fatal drug overdoses. The Monash University study found that, for victims of child sexual abuse, the suicide rates were 18 times that of the general population. For accidental fatal overdoses, victims were 49 times the rate for the general population.[23] And yet for some strange reason a secret internal Victoria Police report, Operation Plangere, discredited Keven Carson’s claim of 40 suicides. While acknowledging the findings of the Cutajar study, the report stated that only one case “had childhood sexual assault by a member of the clergy identified as a contributing factor in the motivations of the person for their death by suicide.”[24] However, there was no actual research undertaken, such as interviews of families of victims, in this flawed report. According to Courtin, “Carson had stated clearly that the information in his reports . . . were never intended to amount to a final and comprehensive report.”[25] These misleading figures were presented to the inquiry in secret and the Operation Plangere report was not made public until 2015.

The final report from the Victorian Government inquiry did, however, make special mention of Courtin’s evidence detailing the disturbing abuse victims received and of the number of suicides and premature deaths of victims.[26]

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse

Courtin’s 71-page submission to the Royal Commission focused the workings of the Towards Healing process. The evidence presented came directly from her doctoral research study and was a damning indictment of the Church’s processes. She summed up her submission in this way:

Towards Healing was designed by the Church and continues to be managed by the Church, and, contrary to the Church’s rhetoric, Towards Healing was also designed for the Church. Victims are, yet again, the abused and exploited players in an unconscionable process.[27]

The Royal Commission recommended oversight by governments for children’s safety and a child-focused complaint handling policy and procedures.[28] Institutions such as the Catholic Church had shown they could not be trusted without this oversight.

Job done? Not yet!

By the end of 2013 with the Royal Commission now underway, Courtin had met her main goal. She considered whether it was worthwhile continuing her doctoral thesis:

I questioned the benefits of continuing with my thesis. But I realised I needed to complete the work. Being the first, comprehensive empirical academic research into Catholic clergy sexual abuse in Australia, it is unique and complements well the growing body of findings from our state and federal inquiries. But, more than anything, I wanted to honour the victims and their families who had brought me into their homes and trusted me, opening their hearts and revealing their pain and suffering and, crucially, telling me clearly what they wanted for justice.[29]

For 2014 there are only three articles mentioning ‘Judy Courtin’ in the ProQuest database? One of these was an op-ed piece she wrote under the heading, ‘The Catholic Church still seems more concerned for its reputation than for its victims.’[30]

So what was Courtin doing? She was actually busy writing her 260-page dissertation which was finally published in 2015 after she was awarded her PhD.[31] There was also a second submission to the Royal Commission made in September 2016.[32]

From 2015 onwards she has now become the ‘go-to person’ for the media looking for comments about the Catholic Church and their response to the Royal Commission recommendations. Although she has originally planned to specialise as a mediator, she now represents victims of child sexual abuse in her own legal practice.

Courtin wasn’t the only person responsible for seeing the ground-breaking Royal Commission established. I’ve previously written about the role of Joanne McCarthy and Anthony Foster. But Judy Courtin played a pivotal role by providing, for the first time, a comprehensive evidence-based analysis of Catholic clerical abuse of children and, more importantly, brought the results of her research to the public’s attention. No easy feat!

None of them would take credit for the achievement. As Courtin said at a conference in 2013:

Victims and their families have in many ways already triumphed. It is their extraordinary courage, their stoicism and their very big hearts that have brought about the Victorian Inquiry, the current NSW inquiry and the Royal Commission.[33]

It will now be up to the Federal and State governments, and the institutions at fault, to implement the recommendations of these inquiries.

You can be sure Judy Courtin will be watching and making herself heard if any further injustice is perceived.

Notes

- “Full transcript: Judy Courtin,” The Age, 25 June 2012, http://www.theage.com.au/national/full-transcript-judy-courtin-20120624-20w4u.html

- Robina Courtin, Robina’s Blog, “Postcard 25 from Robina: Melbourne,” (blog), May 27, 2012, http://www.robinacourtin.com/postcard025.php

- Victoria, Victoria Government Gazette (Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer, October 9, 1986), 84, 3933. http://gazette.slv.vic.gov.au/images/1986/V/general/84.pdf

- Judy Courtin, “Judging the Judges: How the Victorian Court of Appeal is dealing with appeals against conviction in child sexual assault matters,” Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 18, 2 (November 2006): 266-298.

- Victorian Law Reform Commission, Sexual Offences: Interim Report (Melbourne, May 9, 2003).

- Courtin, “Judging the Judges,”.275.

- Judith Edwina Courtin, “Sexual Assault and the Catholic Church: Are Victims Finding Justice?,” PhD diss., (Monash University, October 2015), https://figshare.com/articles/Sexual_assault_and_the_Catholic_Church_are_victims_finding_justice_/4697455.

- Andrew West, “Broken Rites: Unearthing sexual abuse in the Church,” Religion and Ethics Report, aired March 29, 2017 (Sydney ABC Radio National, 2012), Radio Broadcast, http://mpegmedia.abc.net.au/rn/podcast/2017/03/rer_20170329_1755.mp3

- Carrie N. Baker, “Scholar Who Studies Sex Trafficking Wins National Journalism Award,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, May 1, 2011, https://www.chronicle.com/article/Scholar-Who-Studies-Sex/127331

- M.V. Lee Badgett, The Public Professor: How to use your research to change the world (New York: New York University Press, 2015), p.74.

- Badgett, “The Public professor,” 13.

- Nick Mckenzie, Richard Baker and Josh Gordon, “Suicides linked to clergy’s ‘sex abuse’,” Sydney Morning Herald, April 14 2012, http://www.smh.com.au/national/suicides-linked-to-clergys-sex-abuse-20120413-1wzcy.html.

- Hamish Fitzsimmons, “Calls for Royal Commission into Catholic Church,” Lateline, screened Apr 13, 2012 (Sydney, NSW: ABC TV, 2012), Television Broadcast, http://www.abc.net.au/lateline/calls-for-royal-commission-into-catholic-church/3949928.

- Judy Courtin, “The truth deserves a commission,” Sydney Morning Herald, April 14 2012, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-opinion/the-truth-deserves-a-commission-20120413-1wz1s.html.

- Samantha Donovan, “Victoria launches child abuse inquiry,” PM, aired April 17, 2012 (Sydney: Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2012), Radio broadcast, http://www.abc.net.au/pm/content/2012/s3479540.htm.

- Michael Short, “Hell on earth,” Sydney Morning Herald, June 25, 2012, http://www.smh.com.au/national/hell-on-earth-20120624-20wa8.html.

- Judy Courtin, “The unholiest of PR spin,” Sydney Morning Herald, Sep 27, 2012, http://www.smh.com.au/federal-politics/political-opinion/the-unholiest-of-pr-spin-20120926-26N3.html.

- Dan Box, “George Pell feels shame at ‘cancer’ of abuse,” The Weekend Australian, November 10, 2012, http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/george-pell-feels-shame-at-cancer-of-abuse/news-story/dda2be6ca473c665051868cbffb505a8.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Final Report: Preface and Executive Summary (Canberra, 2017), 6, https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/preface-and-executive-summary.

- “The Conversation,” Judy Courtin, https://theconversation.com/profiles/judy-courtin-8743/articles.

- “Australia & New Zealand Newsstream,” ProQuest, http://proquest.libguides.com/anznewsstream.

- Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations, Hearings and Transcripts (Melbourne: Parliament of Victoria, 2013), https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/fcdc/article/1786.

- Margaret C Cutajar et al., “Suicide and fatal drug overdose in child sexual abuse victims: a historical cohort study,” Medical Journal of Australia (MJA), 192, 4 (15 February 2010): 184-187, https://www.mja.com.au/system/files/issues/192_04_150210/cut10278_fm.pdf

- Victoria Police, Review of the Nominated Potential Premature Deaths Related to Child Sexual Assaults (Melbourne, November 1, 2012), 1, https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/VPOL.0017.005.0019_R.pdf.

- Judy Courtin, “Flawed report denies justice to clergy-sex victims,” Sydney Morning Herald, August 10, 2015, http://www.smh.com.au/comment/misuse-of-flawed-operation-plangere-report-cheats-victims-of-ballarat-clergy-sex-20150808-giujol.html.

- Inquiry into the Handling of Child Abuse by Religious and Other Organisations, Final Report Volume 1: Betrayal of Trust, (Melbourne: Parliament of Victoria, November 13, 2013), 80, https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/fcdc/article/1788.

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Issues Paper 2 – Submission – 14 Judy Courtin, September 2013, https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/file-list/Issues%20Paper%202%20-%20Submission%20-%2014%20Judy%20Courtin.pdf.

- :Royal Commission, Final Report: Preface and Executive Summary, 121.

- Courtin, “Sexual Assault and the Catholic Church,” ix.

- Judy Courtin, “The Catholic Church still seems more concerned for its reputation than for its victims,” Sydney Morning Herald, August 25, 2014, http://www.smh.com.au/comment/the-catholic-church-still-seems-more-concerned-for-its-reputation-than-for-its-victims-20140824-107rnj.html.

- Courtin, “Sexual Assault and the Catholic Church.”

- Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, Submission for Consultation paper: Criminal justice 23. Dr Judy Courtin, 4 November 2016, https://www.childabuseroyalcommission.gov.au/sites/default/files/file-list/Consultation%20Paper%20-%20Criminal%20Justice%20-%20Submission%20-%2023%20Dr%20Judy%20Courtin.pdf.

- Judy Courtin, “Sex Crimes and the Catholic Church: Will a Parliamentary Inquiry and a Royal Commission deliver justice to victims, survivors and their families?,” Castan Centre for Human Rights Law Conference, July 25, 2013, https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/138161/courtin-paper.pdf.

Regarding the PMs promise to apologise to the victims of sexual abuse.

Will this include an even bigger apology to victims who took their abusers to Court 20 or more years ago only to be told by the Magistrate that there was ‘no case to answer’.

In my son’s case, Police estimated the Church spent hundreds of thousands of dollars to get this result. All the Church did was strip the man of his high offices and ship him off to the Philippines. The Royal Commission promised my son and his fellow complainants that they would be ‘prime Witnesses’. The strong ones had hope and delayed their suicide attempts.

We have all failed my son. The Church, the police, the psychologists, the law, the commission and especially me. May God forgive us all. We didn’t know what we were up against.

Janetta, I’m also appalled by the amounts of money the Church continues to spend in fighting cases using the highest-paid lawyers available. Only the wealthiest individuals in the country have this luxury.

Thank you very much. Very useful information